By Zinta Zommers, UN OCHA and Perry World House Visiting Fellow

Recent reports by the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), in its Sixth Assessment Cycle, offer a sobering evaluation of the climate related challenges facing Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Indeed, the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, has called the reports a file of shame, stating that, “We are on the fast track to climate disaster”. This brief reviews the risks to SIDS highlighted in the IPCC report on “Impacts, Vulnerability, and Adaption” and reviews opportunities to act earlier, highlighting progress on anticipatory action by the UN and other partners.

Risks

According to the IPCC, increasing weather and climate extreme events have exposed millions of people to acute food insecurity and have reduced water security, with the largest impacts among small island communities. Groundwater availability in SIDS is also threatened by climate change. These impacts will only be exacerbated in future. Above a 1.5ºC global warming level, freshwater resources will dwindle and pose potential hard limits for Small Islands. At 2ºC or higher global warming level, food security risks due to climate change will be more severe, leading to malnutrition and micro-nutrient deficiencies concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Central and South America and Small Islands. In addition to this, sea level rise poses an existential threat, jeopardizing the very existence of some communities and cultures in SIDS.

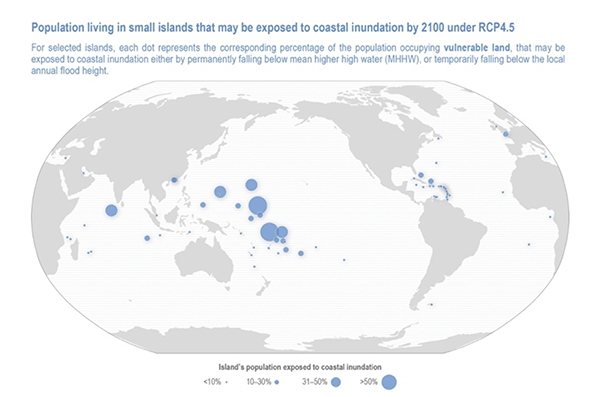

Fig. 1 Projected percentage of current population in selected small islands occupying vulnerable land (the number of people on land that may be exposed to coastal inundation—either by permanently falling below mean higher high water, or temporarily falling below the local annual flood height (Source: IPCC, 2022).

Risks are not driven by hazards alone but by changing vulnerability and exposure. Growing populations and assets along coasts compound challenges. Globally, population change in low-lying cities and settlements will result in approximately a billion people being at risk from coastal-specific climate hazards in the mid-term under all scenarios, including in Small Islands.

Responses

A variety of response options exist to deal with such risks and impacts. While the global community needs to urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions, coastal communities can consider protection, accommodation, and advance and planned relocation. According to the IPCC, these responses are more effective if combined and/or sequenced, planned well ahead, aligned with sociocultural values and development priorities, and underpinned by inclusive community engagement processes. However even with maximum possible adaptation, tropical agricultural deltas and urban atoll islands will face high limits from sea-level rise. Adaptation measures will not be sufficient, and loss and damage will occur. Soft limits to adaptation, resulting from constraints in finance, among others, have already been reached in low lying coastal areas in Small Islands. Available finance is further constrained by crisis, such as COVID-19. In a “post-pandemic world”, a Category 2 cyclone may feel like a Category 5 cyclone, due to limited domestic resources to respond.

Anticipatory Action

It is critical therefore to ensure that financing is available early so communities can take action to minimize shocks. It is also vital that the humanitarian community engage in climate change discussions and policy to help better address losses and damages that will increasingly occur in SIDS. Over the past few years progress has been made in both areas with the growth of “anticipatory action” or “forecast-based finance”. Already in 2014, the UN General Assembly asked the humanitarian system to shift towards an anticipatory approach to prevent and reduce human suffering. There are now anticipatory action pilots in over 60 countries, including Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Fiji.

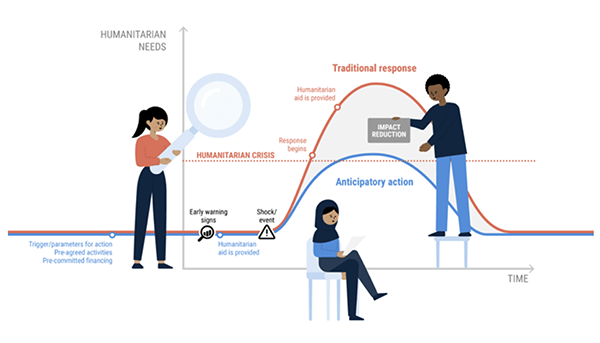

Traditionally, humanitarians respond to disasters by doing a damage or needs assessment and then searching for funding. Anticipatory action (AA) is not based on impacts but on risks. To be successful, anticipatory action requires:

- forecasting that tells us when there is a high probability of a high impact shock;

- pre-agreed anticipatory actions that can mitigate the impact of such a shock; and

- pre-arranged financing.

When a pre-agreed trigger is reached, based on a forecast, finance is released so that communities or humanitarian partners can take actions in advance of shocks. By delivering payments early, AA helps remove some soft limits faced by communities.

Figure 2. The path of anticipatory action vs. traditional humanitarian response (Source: OCHA)

Since 2018, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has worked with donors, implementing organizations (such as WFP, FAO, UNICEF, IOM, UNFPA, and IFRC), governments, and experts to promote change towards a more anticipatory humanitarian system. This included an initial commitment of up to USD 140 million from the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) to develop 12 pilot anticipatory action frameworks for different shocks, including drought, flooding, cyclones, and communicable disease outbreaks. As of July 2020, 2.2 million people in Somalia, Ethiopia, and Bangladesh had been reached through anticipatory action. CERF had spent just over USD 60 million on these pilots, less than six percent of its total spending over the same period. OCHA has also finalized anticipatory action frameworks in six additional countries (Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Nepal, Niger, the Philippines, and Malawi), covering more than 2.3 million people and providing USD 58.5 million of pre-arranged finance for action, should triggers be reached. OCHA pilots have demonstrated that anticipatory action is fast, efficient, effective, and dignified humanitarian action.

The anticipatory approach could be further piloted and scaled to cover all the SIDS. However, measures would have to be taken to improve forecasts, activities, and finance. We need to invest in data collection to help better predict all the shocks that communities face. Hazards such as cyclones are increasingly becoming multi-country events. Frameworks for action must be developed across countries and regions, and pre-agreed activities coordinated across broad geographic areas. We also need to better identify actions that can help address and minimize non-economic losses. Most humanitarian efforts have focused on loss of life rather than on loss of cultural assets or ecosystem services, important issues in climate change discussions. Additionally, more financing will clearly be needed if we are to reach all communities before shocks occur. Pre-determined benchmarks or triggers could be developed not only for cash distribution but also for top-up of funds. Donors could agree to automatically replenish funds such as CERF based on triggers related to climate shocks.

Finally, the humanitarian system cannot act alone. Development planning needs to be more anticipatory as well. Shock-response social safety nets need to be further scaled. Decadal forecasts or long-term changes in extreme event trends could be used as triggers to provide pay-outs for adaptation action. Through its work to develop the Extreme Climate Facility, the African Risk Capacity is piloting such efforts.

In September 2021, 135 Member States, and humanitarian and other actors came together to highlight the need to further mainstream anticipatory action – a significant broadening of political support. AA will not provide all the solutions to the challenges facing SIDS, but when combined with other interventions or as part of a package of layered risk reduction efforts, it could be a useful tool to help minimize losses from the worst climate shocks.

This article was written for Perry World House’s 2022 Global Shifts Colloquium, ‘Islands on the Climate Front Line: Risk and Resilience,’ and made possible in part by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The views expressed are solely the author’s and do not reflect those of Perry World House, the University of Pennsylvania, or the Carnegie Corporation of New York.