By Amica Rapadas and Annie Olise-Aikins

When we think of cities, we might overlook informal settlements – areas also known as slums, favelas, kampongs, or villas. However, over one billion people call them home. As climate change intensifies, residents in these settlements face increased exposure to natural hazards, but they are too often excluded from political systems and social support.

SDG target 11.5 aims to reduce disaster-related deaths and protect the poor and most vulnerable. To that end, inclusive, community-led climate actions in informal settlements are crucial to protect the people who often bear the brunt of climate risks.

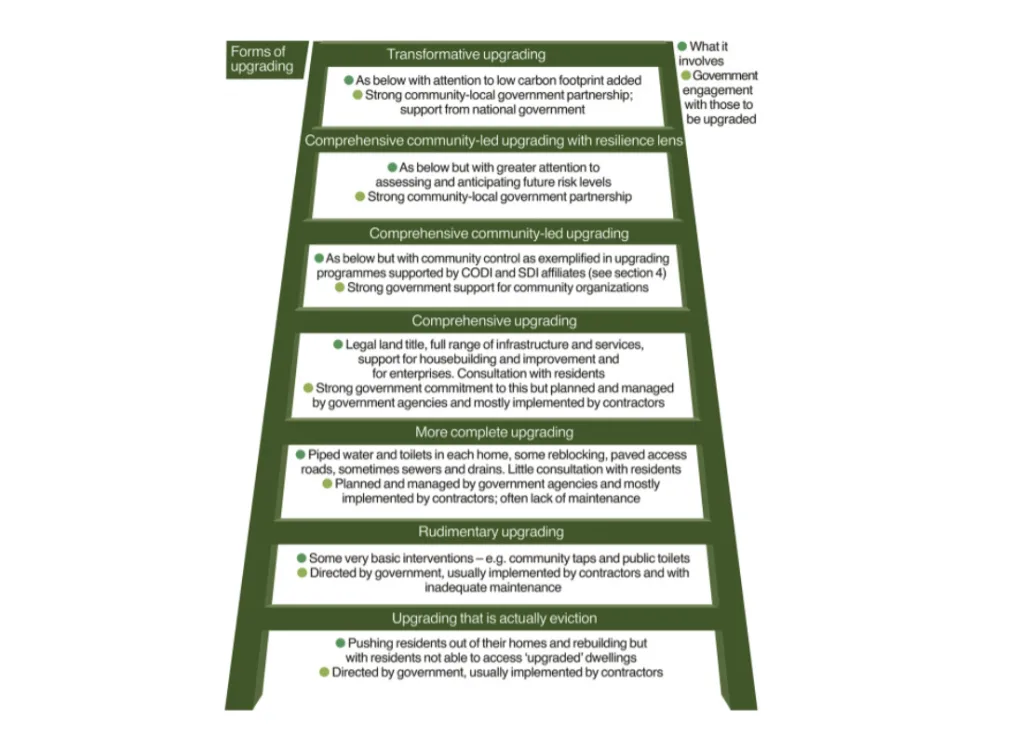

Instead of attempting to “clean up” cities in conventional ways that might displace these communities, resilience efforts should focus on transformative upgrading, which means strengthening the existing infrastructure through participatory approaches. This process calls for fostering strong partnerships between the target community and local and national governments. The ladder graphic below shows how cities and residents can collaborate to transition from eviction as a method of urban cleanup to creating inclusive spaces that safeguard the dignity and well-being of all.

Figure 1: The Ladder of Different Forms of Informal Settlement Upgrading

While transformative upgrading is challenging, communities worldwide have demonstrated it is achievable. Iloilo City (Philippines) and São Paulo (Brazil) shed light on how sufficient housing is a critical entry point to improving urban services and alleviating stresses posed by rapid urbanization. Jodhpur (India) and Fortaleza (Brazil) provide examples of prioritizing an inclusive approach to address informal settlements through collective action strategies.

In Iloilo City, civil society organizations (CSOs) partnered with the local government to provide housing development and rehabilitation services. The city government allocated land, as community groups focused on participatory planning, contributing to SDG targets 10.2 and 10.3. Volunteers established savings groups, lending money to cover household and business expenses. Partnerships between local government, community organizations, and residents (SDG target 17.17) resulted in bettering housing conditions for over two-thirds of the city’s urban poor.

São Paulo is one of the world’s largest cities with striking levels of inequality among urban dwellers. The urban services divide describes the widening gap in resource availability between “better served” populations and almost 1.2 billion “under-served” residents in urban areas.

Residents backed by the São Paulo Alliance of Housing Movements (UNIÃO) have joined together to support various initiatives to improve housing conditions, encourage social justice, and promote environmental protection. One focal housing strategy is self-management (autogestão). This process ensures residents lead decision making regarding unit size, construction materials, environmental preservation, and unit pricing.

A self-managed property in São Paulo’s Northwest region consists of over 500 affordable units and a community nature preserve that adheres to Brazilian areas of permanent protection (APP) regulations. In some housing developments, residents opted to maintain tree nurseries to aid community reforestation. This work not only provides sufficient housing but advances the targets of SDG 13 (climate action). Other dimensions of self-management include promoting widespread accessible energy and improving sustainability through reclaiming vacant structures.

Because residents of informal settlements are excluded from formal support systems, collective action is a powerful tool for empowering these vulnerable communities to lead the changes that benefit them the most.

Across Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, women-led initiatives are making progress in climate resilience for urban poor communities. For example, a network of women energy auditors living and working in informal settlements in Jodhpur are helping their communities gain legal access to clean energy. These women leverage technology solutions to drive climate action that considers both gender and poverty.

Improper waste management is another challenge in informal settlements, and waste pickers are often socially excluded. In Fortaleza the government partnered with the waste pickers association to support these workers by providing training, formalizing their roles, and even equipping them with electric mobility which contributes to reduced inequality.

Socially inclusive housing and community-led collective action initiatives protect informal settlement populations. Increasing their visibility is also a vital component of inclusive urban transformation. This process empowers residents and shifts society away from negative perceptions of historically marginalized groups. The above-mentioned projects are but a few supporting sustainable urban development. Prioritizing transformative upgrading is the push we need to challenge business-as-usual and develop resilient and equitable cities.

* * *

This article was authored by Amica Rapadas and Annie Olise-Aikins. Rapadas and Olise-Aikins are both Masters of International Development candidates at The George Washington University.