The Asia-Pacific region has shown its commitment to more evidence-based voluntary national reviews.

Challenges remain in mobilizing stronger political leadership for data.

A whole-of-society approach is essential to ensure comprehensive monitoring, data inclusivity, and sustainable development for all.

By Arman Bidarbakhtnia, Dayyan Shayani, and Xian Ji

Implementation of the SDG indicators has created a symphony of statistical data management – but not always in sync and not always well orchestrated. It has highlighted the impact of statistics beyond the public policy sphere, potentially enabling meaningful social discourse on development issues and fostering people’s participation in decision-making processes. The support the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) has been providing to SDG monitoring around Asia-Pacific suggests that despite significant improvement in the use of data, and capacity in monitoring the SDGs, there are serious challenges and threats rooted in the institutional set-up of the national statistics systems (NSSs) and data culture among policymakers.

Asia-Pacific’s commitment to SDG monitoring

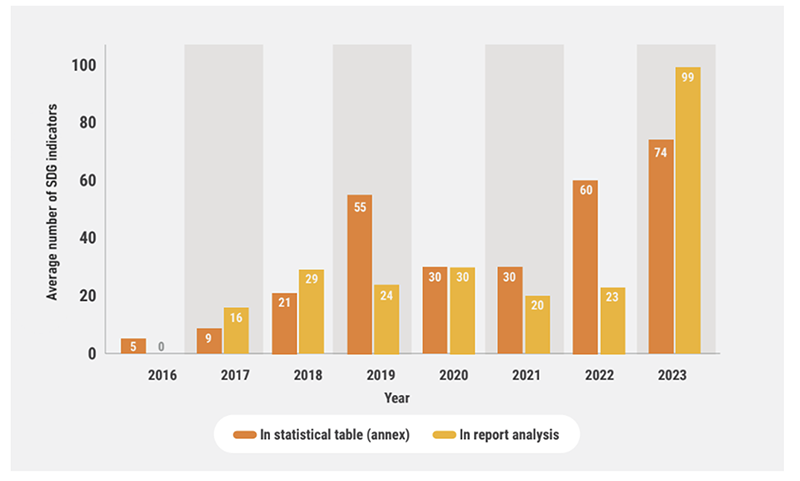

The recent Asia-Pacific SDG progress report reveals that the evidence base in the voluntary national reviews (VNRs) presented by Asian-Pacific countries is expanding. On average, the use of SDG indicators has increased from less than 20 indicators in 2016 and 2017 to nearly 100 in 2023 (Figure 1). The sharp decline in the share of indicators with data that remain unused in VNRs from 88% (2017) to 28% (2023) suggests that the improvement in indicator uptake is not simply due to the availability of more data but rather a shift in attitude towards data in SDG monitoring. The analysis of more than 70 VNRs in Asia-Pacific since 2016 shows a growing inclusion of SDG progress dashboards in the analysis. This shift towards more data-informed reporting practices demonstrates the commitment of countries to evidence-based follow-up and review of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Figure 1. Increased use of SDG indicators in VNRs, 2016-2023

One of the obstacles to utilizing SDG indicators faced by governments is the capacity gap and lack of a standard methodology to summarize the vast amount of information presented by the SDG indicators. In 2023, nearly half of the Asia-Pacific countries presenting their VNR – Brunei Darussalam, Fiji, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Timor-Leste, and Viet Nam – applied ESCAP’s National SDG Tracker to the SDG indicators relevant to their national contexts and created user-friendly dashboards assessing progress against their nationally set target values. This has increased the harmony in reports while they remain relevant to the national policy context.

The roll-out of the SDG indicators and the momentum created by the whole-of-government efforts in VNR preparation have had a positive influence on the culture of evidence-based planning and accentuated the sustainability framework in the national planning processes. Many countries have committed to enhancing their policy monitoring after VNR submission. Some are integrating the SDGs into the planning process, such as Brunei Darussalam’s decision to develop a national sustainability action plan that complements the Wawasan Brunei 2035 Framework and relevant national blueprints, namely economy, manpower, and social. Others took further steps to strengthen the sub-national monitoring mechanisms, such as the Philippines’ decision to use ESCAP’s Every Policy is Connected EPiC tool to develop sub-national SDG catch-up plans).

The Risk of Data Favoritism

While the uptake of the indicators is evident, the gaps or omissions are equally telling in SDG monitoring. Combining the results of SDG data availability assessment and the indicator uptake in the VNRs reveals concerning patterns in prioritization and attitude towards data use.

First, data availability is considerably diverse across the 17 SDGs, with gender equality (Goal 5), life below water (Goal 14), and peace, justice and strong institutions (Goal 16) having fewer than one-third of the indicators with sufficient data. The Asia-Pacific SDG Progress Report 2023 shows the performance of the five countries with the highest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in filling data gaps is worse than the regional average on more than half of the Goals. It suggests that, at least in some cases, the root cause for SDG data gaps may extend beyond limited resources or technical capacity. The nature of Goals 5 and 16, as confirmed in our interaction with governments, suggests that underlying issues are often not recognized as relevant, or given due priority by governments, highlighting a lack of political interest in publicly monitoring those indicators.

Second, further investigation of indicators without sufficient data reveals a pattern that certain topics are more likely to have large data gaps, for instance, public safety (e.g., feeling safe walking alone and experiencing violence), good governance (e.g., public satisfaction, trust, and participation), and human rights (e. g., discrimination and gender equality).

And third, examining indicators with sufficient data that are not included in the VNR reports offers another perspective for identifying potential data favoritism. It is understandable that some indicators are more appropriate for global reporting and have less relevance to national SDG monitoring, such as, for example, 16.8.1 and 10.a.1. Some other indicators may not be picked up by governments due to quality issues, such as the inability to set a target value, ambiguity in the desirable direction, or relevance to the country context. Nevertheless, it is hard to justify neglecting well-defined and relevant indicators with sufficient data, such as 3.4.2 on the suicide rate.

The ESCAP assessment shows that some crucial indicators are rarely mentioned in VNR reports, despite having sufficient data available. Examples include the population living in slums, the prevalence of malnutrition, mortality from unintentional poisoning, and informal employment. Similarly, some indicators related to gender equality such as the proportion of women in managerial positions and women’s participation in decision making are often neglected by governments in their VNR reporting. These are additional reasons to believe there is a tendency to neglect indicators related to somehow sensitive topics even though they are universally relevant.

What is at stake?

Leave no one behind (LNOB) is a fundamental principle of the SDGs. Currently, disaggregated statistics are available only for 29 SDG indicators (out of nearly 70 indicators that could be disaggregated). But the assessment of our performance in meeting the LNOB objective requires more than disaggregated data. Certain issues specific to certain groups are completely missing from the SDG monitoring framework, for example internally displaced people. Additionally, some indicators are too narrow to cover all aspects of targets. For instance, 8.3.1 measures informal employment which is only one aspect of the target. Other issues, including access of micro-, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) to financial services, will not be measured if the monitoring of target 8.3 is limited to only the proposed indicator.

The full understanding of the patterns and interactions between various factors contributing to vulnerability requires applying complex statistical analysis on micro-data (e. g., by using ESCAP’s LNOB tool) and integrating data from various sources.

Finally, the data limitation for tracking progress on the LNOB objective is more evident when SDG indicators are implemented at the sub-national level. Two major obstacles to local SDG monitoring can be described as follows:

- The lack of geographically disaggregated data leaves very narrow evidence space when the data are limited only to the global SDG indicators.

- SDG indicators address broad issues. Many of the development challenges faced by local communities may not be reflected in the SDG indicators and require an expanded set of indicators.

The lack of community and citizen participation in the data lifecycle is an inherent characteristic of state-led statistical systems. This partly explains data favoritism in national SDG monitoring but creates even more challenges as the monitoring gets closer to the grassroots. Local SDG monitoring requires a deeper understanding of the localized issues and more granular evidence (quantitative and qualitative). This demands greater community engagement and stakeholder input, and evidence that goes beyond the SDG indicators and sometimes beyond official statistics (for instance, through public consultations and community feedback).

Power of data for social impact

The lessons from Asia-Pacific suggest that a shift from whole-of-government to whole-of-society approaches is necessary for NSSs to provide the necessary evidence for achieving sustainable development for everyone and everywhere. The key benefit of such an approach is giving voice and agency to all actors, including citizens, the private sector, and academia, for full participation in the entire data value chain. This perspective could lead to improvements in the business process of current state-led statistical systems and inspire efforts to redefine the boundaries of official statistics and establish more inclusive institutions for future systems.

Promising examples, such as the Community-Based Monitoring System (CBMS) in the Philippines, demonstrate the feasibility of bottom-up approaches within current statistical systems. This must be coupled with political leadership, data investment, and transparent governance. This is the main objective of the Power of Data initiative aiming to boost political and financial support for data.

However, relying solely on the current institutional setup of statistical systems is insufficient to meet the data needs for understanding grassroots issues. It is necessary to establish mechanisms that empower non-state entities to act as agents of change in advancing data for better societies. The Power of Data initiative could take more ambitious steps, leveraging the potential of other initiatives, such as the Data Values Project and the Citizen Data Collaborative, and advocate for new statistical systems that officially recognize the role of non-state actors, build new partnerships, and institutionalize community and citizen engagement in the data value chain.

* * *

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organization.

Arman Bidarbakhtnia is Head of the Statistical Data Management Unit at ESCAP’s Statistics Division.

Dayyan Shayani is Statistician at ESCAP’s Statistics Division.

Xian Ji is Consultant at ESCAP’s Statistics Division.