The Paris Agreement has set a new direction and road map for the world. Governments adopted this historical agreement and presented Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that describe their plans and actions towards a cleaner development path, and a more climate-resilient future.

Most NDCs were presented in their original versions before the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties (COP21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in a collective effort to build trust and demonstrate the political will that soon after was galvanized in the Paris Agreement. Before 2020, governments will have an opportunity to update their commitments in order to cover all aspects of climate action.

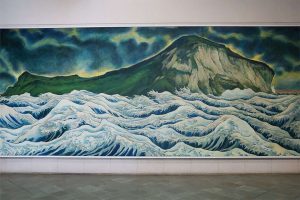

In this regard, one of the greatest challenges we face is the connection between climate action and the ocean.

The ocean plays a critical role in the global response to climate change. It absorbs almost 30% of all greenhouse gases as well as 90% of the excess heat caused by global warming.

However, this comes at a great cost, threatening all the benefits that the ocean provides, and that the international community cannot afford to take for granted. The chemical interaction with CO2 and its absorption in the ocean produces acidification; the ocean also suffers from de-oxygenation as well as sea-level rise, coral bleaching and damage to ecosystems. This threatens food chains, ecosystem services, as well as livelihoods and jobs at a large scale.

With this scenario, governments need to scale up their efforts to conserve marine ecosystems from the impacts of climate change.

The first step that we propose in this direction is to build a strong link between ocean conservation and NDCs, as they are the basic building block of climate action and the main vehicle to implement the Paris Agreement.

Chile, in partnership with France, Monaco, and other countries, has led the “Because the Ocean” declarations, signed during COP21 and COP22. The second “Because the Ocean” declaration was signed in Marrakech by 17 countries, and we expect that many more will join us in the months to come. It is a call to governments to consider ocean conservation as a key element of their NDCs.

We know that linking ocean and climate is as important as it is challenging.

We know that linking ocean and climate is as important as it is challenging. Although the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has already shown consistent evidence that the ocean is seriously affected by climate change, we have a lot of ground to cover before understanding what policies can most efficiently avoid and minimize those negative impacts. Governments will need guidance, and this is why the Special Report of the IPCC on the ocean and cryosphere, to be published by 2019, is great news.

In this regard, the signatory countries of the second “Because the Ocean” declaration state that:

“We would like to underline the importance of the further scientific knowledge that can be brought to light and that it can be critical for us policy-makers, to better understand (1) in terms of mitigation: the biological interactions of marine biodiversity with greenhouse gas emissions and removals and the climate system, and (2) in terms of adaptation: the socio-economic and environmental implications of climate change impacts on the ocean.”

With this in mind, Chile presented a submission to the UNFCCC, arguing that both mitigation and adaptation dimensions need to be taken into consideration for the development of ocean-climate policies.

Recent studies have shown that almost 70% of NDCs presented to date have included, spontaneously (with no guidance from the UNFCCC), a component of protection of coastal ecosystems. Of this total, more than 90% have indicated the intention or the interest in developing adaptation action for the protection of those marine coastal ecosystems. This clearly indicates that there is a vast interest to advance in the link between climate action and the ocean, which makes further knowledge in this field extremely necessary for the design of relevant national policies.[1]

The upcoming United Nations Ocean Conference (also known as the Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources), is a very important opportunity to promote these connections. The Conference includes not only climate-related issues like acidification, but also many other challenges that are climate-sensitive, such as sustainable fisheries, food security as well as the social development of coastal communities, including small-scale artisanal fishers. In this regard, the Ocean Conference is a unique opportunity to underline that climate change needs to be addressed as a crosscutting issue for the health of the ocean. One cannot be achieved without the other.

Chile has taken concrete steps in this direction, creating large Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) around Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Nazca-Desventuradas, promoting conservation and contributing to adaptation to future climate scenarios.

President Michelle Bachelet announced the creation of these MPAs during the Second Our Ocean Conference organized in Valparaiso in October 2015. At that meeting, as well as in the Third Our Ocean Conference (Washington DC, September 2016), the international community consolidated a dynamic process of voluntary actions that are reported transparently and identified opportunities for collaboration. In this regard, the Fourth Our Ocean Conference to be held in Malta in October 2017 will represent an excellent occasion to make further steps in this direction, in particular on the strong relationship between the ocean and climate change.

The challenges ahead are as vast as the ocean itself. As the world shifts towards a more climate–resilient strategy, we need to make sure that our actions are consistent with a healthy ocean. This requires immediate action by all countries, and a common understanding that what is at stake is the well-being of humankind.

[1] Gallo, N.D., Victor, D.G., and Levin, L.A. (in review). Evaluating ocean commitments under the Paris Agreement. Nature Climate Change. (2016).