By Stefan Jungcurt, Lead, SDG Indicators and Data, IISD

Recent reports on progress towards the SDGs are not encouraging. With current trends, the global community will only achieve a handful of SDG targets by 2030, whereas on most targets, progress is either too slow, stalling, or even headed in the wrong direction. A massive acceleration in SDG implementation is needed to keep the 2030 targets relevant. Can this be done?

The short answer is yes, if policymakers are willing to consider the latest evidence on transformation management in their decision making. For the long answer, we must look beyond incremental change to understand how societies can achieve rapid transformations for SDG implementation.

Transformations are “processes of deep, sustained, and nonlinear change in a society’s social and economic structures.” They can result in step changes towards more sustainable outcomes in a particular system like energy, transport, or food. The Global Sustainable Development Reports (GSDR) of 2019 and 2023 review available evidence on the science and practice of transformation management, producing a practical framework. This Policy Brief explores how policymakers can use the framework to accelerate SDG implementation.

Managing transformations

Transformations are common in societies, often caused by the emergence of new technologies or the rise of new behaviors, for example in response to shocks that trigger changes in values and cultures. In the past, transformations were mostly considered spontaneous phenomena over which policymakers have little control and which they should adjust to rather than steer. This perspective is influenced by economic concepts such as the theory of creative destruction that views the supplanting of an existing technology by a superior one as a natural process that frees up resources tied up in the existing system that can then be allocated to better uses. The problem with this view is that it does not consider the appropriateness of the emerging system from a sustainability perspective nor possible negative impacts and trade-offs. It also leaves the speed of systems change to market forces alone.

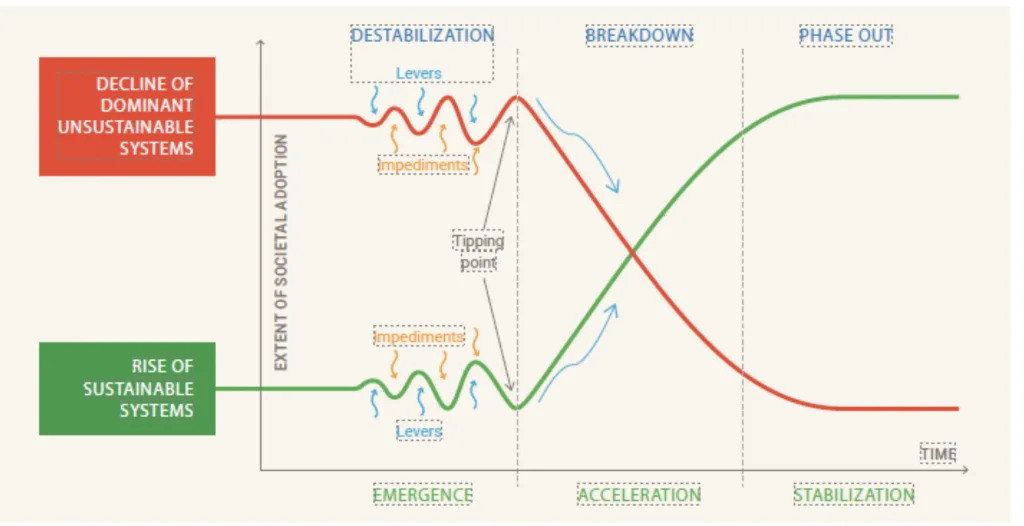

In contrast, the GSDR framework is both more holistic – and more optimistic – about policymakers’ ability to initiate transformations and steer them towards desirable outcomes. The core of the framework is a graph with two intersecting S-curves (Figure 1). The rising curve describes the emergence of a new system in three stages: emergence; acceleration; and stabilization. In a mirror image, the falling curve describes the decline of the existing system from destabilization to breakdown towards its eventual phase-out.

In the emergence/destabilization phase, new technologies and practices appear in niche areas. Think of the first electric vehicles (EVs) that had limited range and were mostly used as second cars by families for short daily trips only. In the acceleration/breakdown phase the new technology or practice matures so that it can fully replace the existing ones in all areas of the system. Adoption increases to a level that has a recognizable impact on the existing system. In some countries like Norway, the Netherlands, and Sweden, EV performance and costs have become comparable to gasoline-powered cars through abundant charging infrastructure and reasonable electricity prices so that EVs now approach 50% of new car sales. In the stabilization/breakdown phase, the technology or practice takes over and pushes the existing system to the fringe. The sale of compact discs for example has declined rapidly since subscription streaming services became widely available, making the purchase of discs impractical and unnecessary.

This dual S-curve framework can be used to assess when and where transformations are taking place and monitor their progress. Importantly, it reminds decision makers that there are two sides to a transformation that both offer opportunities for interventions. The report also shows that the mix of the most effective interventions changes as the transformation unfolds. Policies and measures must thus be reviewed and adapted regularly. Policies to support energy transitions, for example, have for a long time focused on supporting research, development, and commercialization of clean energy technologies. As these technologies have matured, the focus has shifted to supporting infrastructure investments, such as electricity grids, necessary for large-scale adoption. At the same, policymakers are encountering resistance from companies and individuals whose economic fortunes are tied to the fossil fuel system, creating new challenges for policies that ensure a fair energy transition.

The GSDR organizes the range of available interventions and measures into five policy levers. For each lever, the report outlines interventions to consider in each phase of the transformation:

- Interventions included in the governance lever change from supporting the development of a common vision and goal setting in the emergence phase to investing in new infrastructure and managing conflicts during acceleration, to policy and legal reforms that institutionalize the new system in the stabilization phase.

- The focus of the economy and finance lever evolves from supporting prototyping and commercialization of new knowledge, to a larger-scale shift and realignment of support from the old system towards the new one, to adjustments in tax and social support systems to offset possible declines in government revenue and even out disproportionate impacts of the transformation.

- The science and technology lever suggests governments can stimulate innovation through SDG-earmarked research funding in early stages of a transformation. Once new technologies emerge, the focus should shift to standardization of technologies and associated infrastructure. Additional targeted research may be necessary to address remaining barriers during the stabilization phase.

- The policy lever on individual and collective action suggests policymakers encourage and engage with social movements pushing for the desired change throughout the transformation process, including by safeguarding civic space for participation. In the acceleration phase, regulation may be needed to directly incentivize behavior shift.

- The capacity-building lever emphasizes the need for a long-term strategy that continuously creates and retains new skills needed. Initially focusing on supporting innovation and effective governance, capacity-building strategies should plan for skills needed to scale a new system, including abilities to coordinate actors, resolve conflicts, assess impacts, and ensure continuous learning and course correction. Stabilizing the new system requires support for the creation of resilient and adaptive institutions, strategies, and networks.

Policymakers can apply these levers to one or several transformation entry points – issue areas or sectors that have a potential to create synergistic benefits for multiple SDGs. The GSDR authors suggest six broad entry points, noting that focus and scope will vary according to the national context: human well-being and capabilities; sustainable and just economies; sustainable food systems and nutrition; energy decarbonization with universal access; urban and peri-urban development; and global environmental commons.

The entry points build on the universal and interlinked nature of the SDGs where progress towards one Goal can contribute to or unlock synergistic progress towards other SDGs. A holistic perspective will also reveal potential trade-offs with other SDGs and potential negative impacts on population groups depending on the existing system, enabling early intervention to mitigate these effects. The entry point on food systems and nutrition, for example, builds on the connection between food production and human and ecosystem health. A sustainable supply of nutritious food is essential for the well-being of people. At the same time, a shift in dietary preferences from animal to plant-based protein can reduce agriculture’s impact on ecosystems and mitigate its contribution to climate change.

Governments can thus use the GSDR framework to identify promising entry points in their countries and deploy selected interventions under each lever to stimulate, accelerate, and stabilize transitions.

So, what do policymakers think of the framework?

In October 2024, representatives from governments, civil society, and academia from the Asia-Pacific Region gathered in New Delhi, India, to learn about the GSDR framework, share experiences, and discuss how the GSDR framework can support integrated SDG implementation in their countries. Most participants welcomed the framework as a useful tool to assess ongoing efforts and generate ideas and strategies to accelerate progress. The experiences shared showed that many countries already apply some elements of the framework in the national context. For example:

- Nepal has incorporated a national strategic vision of SDG acceleration in its 2023 voluntary national review (VNR), including seven priority themes that were identified using indicators of areas lagging, clustered into themes for action.

- Sri Lanka is using SDG budget tagging to align government spending and has established a national SDG coordination mechanism for vertical and horizontal policy coordination, which has developed integrated solutions for water management and decarbonization.

- India has developed a multi-level approach to support SDG implementation in different regions, states, and cities through targeted interventions, including a regional program for north-eastern states and an urban SDG index supporting progress across 56 cities.

- The Malaysian Government is supporting grassroots social innovation to promote local entrepreneurship for technology adoption and locally driven economic development through a social innovation policy, supported by an associated fund.

Workshop attendees also discussed elements of the GSDR framework that may need to be strengthened or refined to ensure effective transformations that leave no one behind, such as:

- The fundamental importance of a whole-of-society approach that can forge consensus and garner broad support for societal transformations. This can be achieved through inclusive processes that actively engage all population groups that are likely to be affected, negatively or positively.

- The need to ensure that the benefits of transformations reach all population groups and that all are protected against negative impacts, especially marginalized groups that have been left behind in the past. Doing so requires addressing gaps in data describing the status, perspectives, and needs of marginalized groups, which are often excluded from or underrepresented in national statistics. Citizen data can be a tool to address these gaps.

- The role of VNRs as forward-looking documents that should support strategy development and planning, based on a realistic review of progress and analysis of challenges encountered.

- The importance of international donors recognizing the country-led nature of SDG implementation and shifting priorities towards country-led development agendas.

Overall, participants felt that the GSDR framework is a useful starting point for governments and policymakers to develop strategies for accelerated and integrated SDG implementation that build on the theory and practice of transformation management. They also recognized that transformations take time and require long-term strategic planning extending beyond the current 2030 deadline of the SDGs.

The third volume of the GSDR is slated for release in early 2027, in time to inform the third SDG Summit, which will also begin discussing the future of the SDGs. Policymakers from all countries should use the time to 2027 to kickstart SDG transformations to collect practical evidence to refine the framework and maximize our collective changes to make meaningful progress before 2030.