When it comes to exposure to chemicals of concern (CoC), children are one of the most vulnerable populations due to their rapid metabolic rate, high surface-area-to-body-weight ratio, and rapid growth of organs and tissues. Despite this, some CoC have been used in the manufacturing and production of toys. Young children put toys in their mouths and chew on them. They can also be exposed through inhalation and contact with the skin. Parents should not have to worry whether the toys their children play with pose a risk to their health.

Like many consumer products, toys are composed of a range of materials, such as plastics, textiles, and metals. The chemical composition of toys is often not known, and some of the chemicals that are present in toys, may have hazardous properties. Increased circularity and recycling rates of materials, for example, can lead to the introduction of hazardous chemicals as unintentional contaminants to the toys value chain. CoC in toys often enter the lifecycle during plastic production, painting, and coating, or through recycled plastic materials.

While CoC provide toys with certain functions such as fragrance, color, and plasticity, exposure can result in long-term health effects for children, interfering with the hormone system or cognitive development. Such chemicals include mercury, lead, arsenic, and cadmium. Lead affects brain development. Cadmium (found, for example, in batteries) is an endocrine disruptor that affects reproductive development. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs), like phthalates, are associated with higher rates of childhood cancer and endocrine disruption.

Since children are more vulnerable to the health impacts of such CoC, their use in toys is regulated, although that does not mean that, in practice, such chemicals are not present. For this reason, the Strategic Alliance for International Chemicals Management (SAICM) considers toys a priority sector under its Chemicals in Products (CiP) Programme, which aims to accelerate the adoption of measures by value chain stakeholders, including governments, to track and control chemicals in the toy supply chain.

This policy brief explores efforts and initiatives to advance the issue of CoC in toys, particularly under the Global Environment Facility (GEF)-funded project on Global Best Practices on Emerging Chemical Policy Issues of Concern under SAICM, launched in 2019. The project focuses on: lead in paint; chemicals in products, including toys, electronics, textiles, and building and construction; and knowledge and stakeholder engagement. Implemented in over 40 countries, the project also seeks to contribute to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the achievement of the SDGs. The brief highlights relevant tools and reports, as well as recommendations and opportunities the newly agreed Global Framework on Chemicals, the successor to SAICM, provides.

Impacts of CoC in toys

In 2006, one of every three toys in a study of 1,500 had potentially harmful lead, arsenic, and mercury. A four-year old boy in Minnesota, US, accidentally swallowed a heart-shaped locket that had broken off from a bracelet. Instead of passing harmlessly through the boy’s system, the locket contained a high concentration of lead. The boy died.

In 2021, US Customs and Border Protection seized a shipment of children’s toys from China, determining the items were “excessively” coated in unsafe levels of heavy metals, including lead and cadmium. The shipment included nearly 300 packages of Lagori 7 Stones, a popular children’s game in India where a ball is thrown at seven stacked square “stones.”

In 2022, a report published by the Campaign for Healthier Solutions found that harmful chemicals in toys were prevalent in US discount stores. Of the more than 200 tested products, more than half had at least one CoC, such as lead and/or phthalates, present in colorful baby toys and Disney-themed headphones, for example. Costume products like fake teeth made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) can contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals, potentially harming reproductive and cognitive development.

More recently, the EU announced its aim of banning harmful chemicals, especially those that disrupt growth hormones, in imported toys under new rules proposed by the European Commission in July 2023. The Commission’s proposed Toy Safety Regulation aims to address loopholes in existing legislation that dictates safety standards in toys sold in the EU. For some chemicals, regulations in different countries are aligned, but differences remain in many areas between chemical requirements of toy safety policies. For example, the EU Toy Safety Directive severely restricts chemicals known, presumed, or suspected to have carcinogenic, mutagenic, or reprotoxic effects for use in toys. This differs from a chemical-by-chemical approach applied in many other toy safety regulations.

SAICM efforts to address CoC in toys

Although highly regulated in the EU, the US, and other developed countries, CoC in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are another matter. A 2021 SAICM/GEF project report reviews chemicals-related toy safety policies and regulations in selected LMICs, providing an overview of safety policies addressing CoC in toys and detailing activities SAICM should prioritize in those countries. The report focuses on those LMICs with the highest total import value of toys from China. The middle-income countries (MICs) reviewed (Brazil, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, the Russian Federation, Thailand, and Viet Nam) have toy safety policies with provisions for the content of certain chemicals in toys, namely on material-specific migration limits for antimony, arsenic, barium, cadmium, chromium, lead, and selenium. In the low-income countries (LICs) reviewed, Tajikistan and Tanzania have some existing regulations. However, no information was found regarding toy safety policies in the other LICs, including Benin, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Guinea, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Madagascar, Mozambique, Syria, and Yemen.

Other project outputs include a report on regulations for chemicals in toys in China, which provides an overview of related regulations that dictate the use of chemicals in toys produced in China, and a USEtox toys module, developed to help producers assess chemicals used in toy components and potential risks for children. USEtox is a scientific consensus model for characterizing human and ecotoxicological impacts of chemicals.

In addition, a 2021 UN Environment Programme (UNEP)-commissioned report, undertaken by the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), found that 25% of children’s toys contain harmful chemicals. According to the report, chemical additives used in plastic toys that provide certain properties, such as hardness or elasticity, include plasticizers or softeners, flame retardants, surface-active substances (to create foam), stabilizers, colorants, and fragrances. While softer plastic toys lead to higher exposure to harmful chemicals than hard toys, exposure from inhalation is more prevalent than touching since children inhale chemicals diffusing out of all toys in the room. The report recommends ensuring children’s rooms are ventilated to avoid the inhalation of dangerous chemicals. Acknowledging that avoiding all plastic toy use would be difficult, it recommends prioritizing substances for phase out in toys and replacing them with safer alternatives.

The study explains that:

- since most plastic toys are not labelled, parents do not know whether an item is harmful;

- currently, no international agreement exists regarding which substances should be banned from use in toys;

- regulations and labeling schemes differ across regions and countries; and

- existing priority substance lists lack information on levels at which use of a CoC is safe and sustainable in product and material applications.

Researchers combined reported chemical content in toy materials with material characteristics and toy use patterns, such as how long a child plays with a toy, whether he/she puts it in the mouth, and the number of toys per household per child. Based on this, the study introduces a new metric to benchmark chemical content in toys, based on exposure and risk.

A SAICM policy brief aims to enhance understanding of CoC in products, and efforts to reduce them in toys, textiles, buildings and construction, and electronics. It notes that transparency of information about chemicals in global supply chains has been an emerging policy issue under SAICM since 2009. This led to UNEP’s CiP programme in 2015, under which SAICM proposed cooperative actions to address information gaps regarding the presence of hazardous chemicals in the four sectors.

The policy brief details measures to reduce CoC through:

- legislation and information system tools, such as regulations, standards, and certification mechanisms;

- holistic tools that consider the entire value chain, such as life cycle assessment tools and eco-innovation;

- production tools that seek to minimize exposure and focus on cleaner and responsible production; and

- consumption tools that focus on consumer behavior, including sustainable public procurement and ecolabels.

UNEP, in collaboration with the Baltic Environment Forum and within the framework of the SAICM/GEF project, developed an International Chemicals Management Toolkit for the Toys Supply Chain to facilitate regulatory compliance in the toy sector. Providing useful information, guidance, and tools, the toolkit aims to support stakeholders in the toys industry at multiple stages of the value chain, including:

- manufacturers of toys or toy parts from plastic pellets;

- assemblers of toys from individual parts;

- importers and retailers of toy products; and

- policymakers in the field of chemicals management, toy or product safety, and/or the toy value chain.

The toolkit aims to help stakeholders track and manage chemicals in toys, fulfil chemicals-related legal obligations, and ultimately protecting children from CoC in toys. With a focus on raising awareness on occurrences and risks related to CoC in toy materials at the early stages of the value chain, the toolkit: informs users on how to employ substitute and alternatives; presents guidance on how to convey information to consumers; and provides information, tips, and guiding questions for stakeholders interested in going further than regulatory compliance.

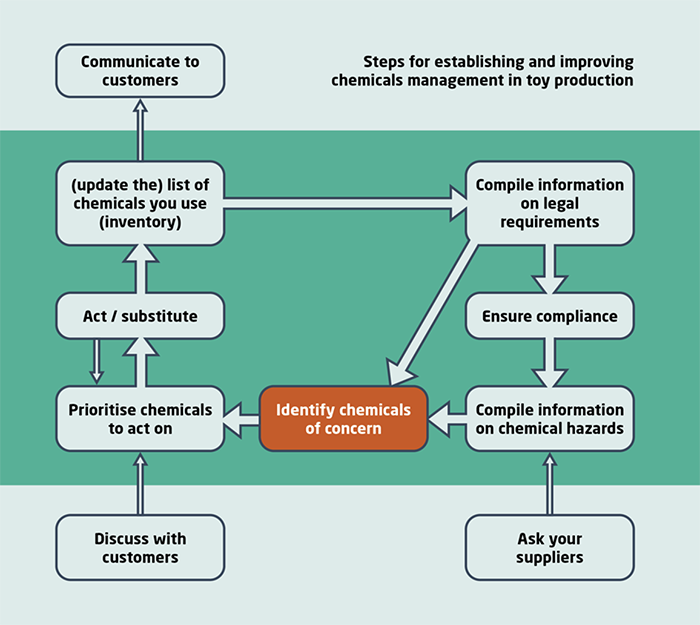

Figure 1: Steps for establishing and improving chemicals management in toy production

Source: SAICM

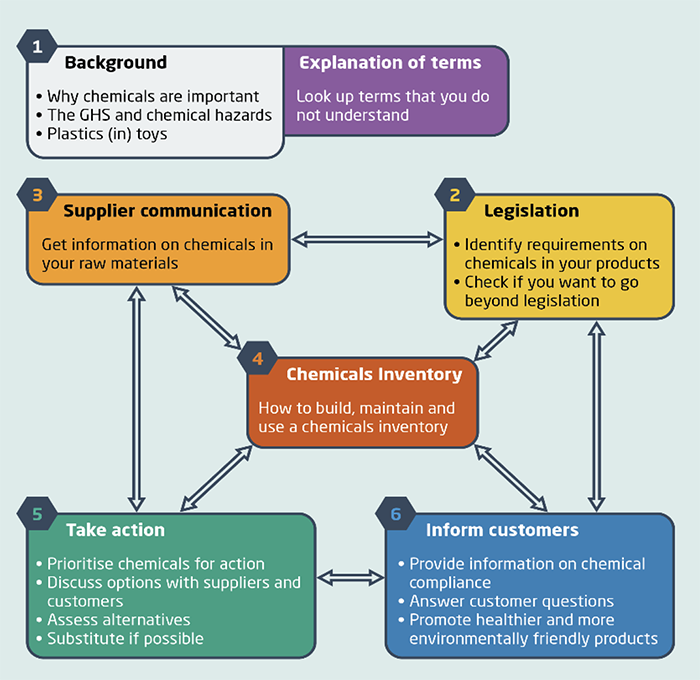

Based on the steps described in Figure 1 above, the toolkit’s sections (see Figure 2 below) elaborate on the steps:

- Compile background information, including on the challenges of CoC in toys, plastics and the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), and information on the risks and effects of CoC in the toys supply chain;

- Compile information on legislation and identify regulatory requirements for chemicals in toy products, depending on where the toy is placed on the market;

- Establish good, clear, and efficient communication with suppliers, for example, to get information on chemicals or to discuss potential quality problems with them;

- Build or review an inventory of chemicals in raw materials and in products, explain why such a chemical inventory should be used, and make the best use of it;

- Take action, including using guidance and tools for replacing a CoC with alternative chemicals, another technology, or a different material; and

- Inform customers by providing guidance on how to communicate on chemicals-related issues with downstream supply chains and end-use consumers.

Figure 2: Toolkit sections

Source: SAICM

As mentioned above, when children are young, they mouth toys, teethers, and pacifiers, all of which contain different chemical additives such as plasticizers, flame retardants, and antimicrobials that help optimize specific properties. However, many of these additives migrate from products into saliva since they are not covalently bound to the polymer chains. While assessing exposure pathways in children is crucial, pathways such as mouthing are often poorly quantified or neglected. In light of this, a study on Estimating mouthing exposure to chemicals in children’s products, supported by the SAICM/GEF project, developed a model to predict migration into saliva, mouthing exposure, and related health risks of different chemical-material combinations in children’s products. The study adapted an earlier migration model for chemicals in food packaging materials, as well as a regression model based on identified chemical and material properties. The model represents a green and sustainable chemistry tool that industries can apply to assess whether the chemicals in their products could pose a risk to children, as well as to evaluate safer alternatives during the design process.

In June 2023, SAICM convened a multi-stakeholder virtual Workshop on Tools and Guidance to Manage Chemicals in Toys to present the tools and guidance developed throughout the SAICM/GEF project’s duration, share key lessons from the project, and facilitate the exchange of knowledge and best practices among stakeholders. It was targeted at stakeholders working to enhance toy safety, including: industries in the toy value chain, such as raw material suppliers and manufacturers; retailers; regulators and government representatives; international standardization organizations; and civil society representatives.

Continuing to reduce CoC in toys going forward

According to the UNEP-commissioned DTU report, international standards are a key entry point for countries establishing chemical-related toy safety policies. To ensure success, standards and trade policies must be ambitious and flexible. They must facilitate the establishment of stricter safety requirements. Compliance and enforcement are also key to protecting children from chemicals-related risks in toys. Toy manufacturers must understand the regulatory requirements of the markets they are selling to. In addition, countries manufacturing or importing toys should establish enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance with local regulatory requirements. However, small and medium-sized companies or companies not integrated into highly controlled supply chains of original equipment manufacturers or large retailers will face challenges that must be overcome.

It is also important to enhance collaboration among stakeholders in the toy value chain and improve synergies among regulatory requirements, industry capacity for compliance, transparency along the supply chain, and coordinated enforcement.

For example, in the EU, consumers have the right to know about the inclusion of harmful chemicals in products sold in Europe and the right to ask for information about them. Consumers can contact producers directly or do so through platforms like the Scan4Chem app if they suspect a product may contain chemicals above a certain limit that could be harmful to health and the environment. Substances of very high concern (SVHCs) are included in the EU’s REACH Candidate List of SVHCs. By law, suppliers must provide this information, free of charge, within 45 days from the date of request. The right to know applies to toys, as well as textiles, furniture, shoes, sports equipment, toys, and electronic equipment.

Other recommendations from the DTU report policymakers and other stakeholders could take onboard include the following:

- Countries should align policies targeting circularity and CoC, for example banning the use of recycled plastics in the manufacturing of toys or strictly controlling the source. Children’s toys made from recycled plastic contain toxic flame-retardant chemicals OctaBDE, DecaBDE, and HBCD. High concentrations of the toxic chemicals have been found in, for example, the Rubik’s cube toy, with 90% of examined cubes containing OctaBDE and/or DecaBDE. Toxic chemicals end up in toys when electronic equipment casings are used in recycling processes. Although the use of toxic flame retardants is prohibited in the EU, plastic recycling often happens in African or Asian countries where regulations are less strict, with chemicals ending up back in the supply chain. Thus, products made from recycled plastic should not be allowed to contain high concentrations of flame retardants, electronics casings should be removed before recycling, and stronger international limits on hazardous chemicals are needed.

- When adopting regulatory action, policymakers must ensure coherency across different regulatory domains, for example on products, chemicals, and waste, as well as across countries and regions, given the global flows of materials, products, and waste. Regulations and policies should be ambitious, as well as flexible enough to facilitate, rather than hamper, the establishment of stricter safety requirements where needed.

- Policymakers could establish platforms for training, dissemination, and information exchange related to CoC and for raising awareness about the risks from CoC for all stakeholders. Upstream small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and e-commerce could benefit from training on relevant regulations, laboratory testing, and customs rules, while policymakers would benefit from the dissemination of good practice policies.

The new Global Framework on Chemicals presents further opportunities to address CoC in toys. For example, participating governments have pledged to create a regulatory environment to reduce chemical pollution and promote safer alternatives by 2030, while industry has committed to responsible chemical management to reduce pollution and its adverse effects by 2030.

* * *

This document has been developed within the framework of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) project ID: 9771 on Global Best Practices on Emerging Chemical Policy Issues of Concern under the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM). This project is funded by the GEF, implemented by UNEP, and executed by the SAICM Secretariat. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) acknowledges the financial contribution of the GEF to the development of this policy brief.

This Policy Brief is the ninth in a series featuring cross-cutting topics relating to the sound management of chemicals and waste. It was written by Leila Mead, Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB) team leader, editor, and writer. The series editor is Elena Kosolapova, Senior Policy Advisor, Tracking Progress Program, IISD.