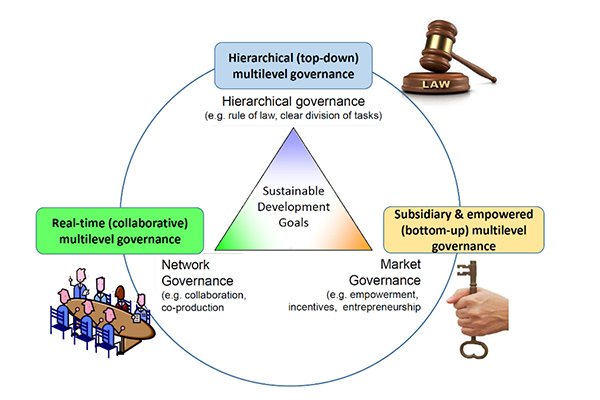

The Goals and visions of the 2030 Agenda are agreed at global level, but a large part of their implementation takes place locally. To make things work, we need all levels: the bold decisions required to achieve the SDGs can only be carried through when those who are governed feel included and understood by those who govern. SDG 16 calls for effective institutions at all levels, and progress towards this Goal will be reviewed during the July 2019 session of the UN High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF). One determinant of effectiveness is the way institutions work together across levels. This article explains three approaches to this “multilevel governance,” and indicates how they can be combined to serve the SDGs.

Between global and local authorities stand national and subnational authorities, who provide the “translation” of broad ambitions into concrete tasks. These are transferred as mandates for implementation at a local level. The relations between all these levels are called multi-level governance, and it typically operates in one of two ways: either top-down or bottom-up.

Top-down Multilevel Governance

The first approach is characterized by a hierarchical mind-set regarding the levels. This has several benefits: it emphasizes rule of law and offers a clear structure. It defines responsibilities and provides stability. It is usually slow, but that can be a positive quality in governance, as frequent changes in policy and law can create unpredictability for citizens and businesses.

Nevertheless, it often takes many years before a proposed policy or legal agreement decided at the top “trickles down” to concrete implementation by local authorities. In the EU, there is even an additional legislative level, which can add years to the decision-making process. At the same, time speed can be important in order to avoid high environmental, social and economic costs of non implementation.

Bottom-up Multilevel Governance

The second approach is based on subsidiarity and empowerment. In the EU, subsidiarity is enshrined in the Treaty on the European Union. It aims to ensure that decisions are taken at the most “appropriate” level, with appropriateness referring to the capacity and relevance of each governing level to make decisions on an issue, and implement the related policies. Empowerment makes bottom-up governance more effective, since measures can be taken at the lowest level where they can be implemented sufficiently.

Empowering subsidiary levels of government has led many cities to become hotspots of sustainability innovation. It has also stimulated them to form networks such as the Covenant of Mayors on climate change. The bottom-up mindset can be instrumental in fostering inclusive local governance, promoting ownership and enhancing co-production and customization of policies and services. Empowerment of local governments is important because those authorities are best placed to understand their communities’ needs. However, this approach can be a slower way to scale up good practices, while economies of scale may be able to do so more quickly. The approach also requires higher administrative levels to alleviate financial or legal constraints for the lower levels.

Real-time Multilevel Governance

Both traditional approaches to distribute remits across governance levels result in a slow transfer of ideas: a hierarchical system can be slow to transfer ideas from the national to the local level, while subsidiarity tends to delay innovations’ move from local to national level, and beyond. But need we restrict ourselves to two methods? This reminds me of the last automobile that was produced (until 1980) in the Netherlands. The DAF 66 was notorious because it had only two gears: forwards and backwards. Top-down and bottom-up, or forwards and backwards: sometimes we just need more variation.

Fortunately, a third approach is developing, which can be called real-time collaborative multi-level governance. This requires stepping out of comfort zones as, for urgent issues, government bodies would establish mechanisms for “real-time” cooperation between all relevant levels. Working together on urgent challenges simultaneously could involve, among other tools, the use of digital platforms to receive and collect data on policy and service delivery issues and to keep track of actions taken towards resolution of challenges with transparency and accountability.

This approach is highlighted in the contribution of the UN Committee of Experts on Public Administration (CEPA) to the July 2019 session of the HLPF, and also in a recent report from the EU Committee of the Regions. Examples of the approach being put into practice can be found in the database of SDG good practices, the Knowledge Base of UN Public Service Awards Initiatives, and the 2018 World Public Sector Report. Examples from around the world include:

- In the Netherlands, “inter-administrative dossier teams” between national, regional and local authorities already exist, and this could be a good practice to learn from.

- SDG implementation can be monitored at the sub-national level through: central government efforts; sub-national monitoring structures; or joint, multi-level structures and mechanisms, as found in several European and Latin American countries. In Colombia, multi-level processes enable allocation of budget resources across territories and establish common reporting formats.

- The Republic of Korea, like many Asian nations, has traditionally had very fixed roles for government and residents, with civil society primarily focused on public policy. The Do Dream project has changed all that. No longer do city staff ignore issues that are “not part of my job.” No longer are governmental resource systems considered separate from private donations, NGO programs, and higher-government programs, instead these resources are interwoven to maximize benefits to the needy, according to the Korean government.

The Trick? Combine the Three Approaches

The three approaches represent three distinct governance styles which are based on, respectively, rule of law, empowerment and incentives, and collaboration and co-production. Theory and practice of metagovernance (governance of governance styles) shows that, ultimately, we need all three approaches. The real-time collaborative approach will not replace but is an important addition to the classical styles.

The approaches complement but can also undermine each other, depending on how they are combined and on the context in which they are used. The traditional approaches can be too slow to address urgent and complex problems. The third way seems faster, but can be undermined when distrust replaces trust, or when incentives lead to competition between authorities.

The trick will be, as Davis and Rhodes (2000) have argued for public sector reform in general, “to mix the three systems effectively when they conflict with and undermine one another.” Then we can avoid the sort of outcome obtained by DAF and have a vehicle with a three-speed gearbox for implementation of the 2030 Agenda by all public sector levels.

The author of this guest article, Louis Meuleman, is a member of the UN Committee of Experts on Public Administration (CEPA). He also is affiliated with Leuven University, Wageningen University & Research, and University of Massachusetts Boston.