By Jorden de Haan

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) is a largely informal industry, known for its close relations with armed conflict, organized crime, human rights abuses, and corruption. But the sector is also a critical engine for rural development in the Global South.

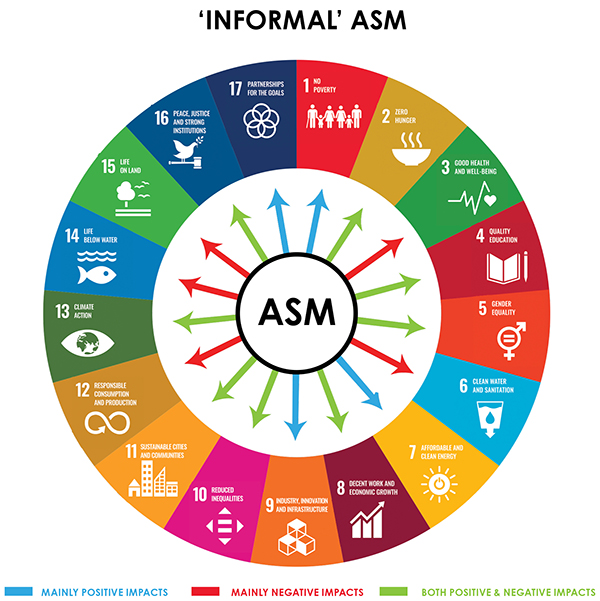

The world’s first complete ASM-SDG assessment, published in September 2020, finds that the sector has both negative and positive impacts across the SDGs. And a recent book chapter on SDG 16 demonstrates how inclusive formalization processes could unlock the sector’s potential in supporting peaceful, just and inclusive societies.

Perceptions in Need of Reversal

The role of ‘blood diamonds’ in fuelling the civil wars of Angola, Sierra Leone, and Liberia has become a textbook example and a Hollywood blockbuster. So-called ‘conflict minerals’ from the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have led to international policy mechanisms promoting due diligence in mineral supply chains, and the recent upsurge of extremist groups targeting gold mines in the Sahel to finance terrorism is sparking increased media attention. Besides this, ASM tends to be criticized (and even criminalized) for negative environmental and health impacts, with little consideration of its potential.

ASM and the SDGs

However, as evidence overwhelmingly suggests and as policymakers increasingly recognize, the sector is a critical engine for rural development in the Global South. In fact, as we demonstrate in Mapping Artisanal and Small-scale Mining to the Sustainable Development Goals published by Pact and the University of Delaware, even if informal, the sector has positive impacts on almost all 17 SDGs.

Informal ASM-SDG Relations. Image credit: de Haan, Dales & McQuilken, 2020

Straightforward examples include SDGs 1 (no poverty) and 8 (decent work and economic growth), as the sector provides direct, economically viable livelihoods for more than 42 million women and men living in impoverished areas.

A more surprising example, but one that is gaining traction, is the ASM sector’s production of minerals that are critical for the transition to clean and renewable energy systems, such as cobalt and copper. By extension, mining of those key production elements will help mitigate climate change, as reflected in SDGs 7 (affordable and clean energy) and 13 (climate action).

ASM and SDG 16

The SDG that seems like the most unlikely fit for ASM – given its associations with conflict minerals – is Goal 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions).

A dumpsite for targets and indicators on peace, security, human rights, inclusion, and good governance, SDG 16 is arguably the most challenging of all of the SDGs to implement. Since the adoption of the 2030 Agenda in 2015, yearly Reports of the Secretary-General on progress towards the SDGs have constantly reported insufficient and uneven progress on SDG 16. COVID-19 exacerbates this trend, with spikes in violence against women and excluded minorities, and governments clamping down on civic freedoms under the guise of a public health crisis. This poses a threat to all SDGs. After all, as the 2030 Agenda recognizes, “There can be no sustainable development without peace, and no peace without sustainable development.”

Even in its largely informal state, ASM supports SDG 16’s three key domains of peace, justice, and inclusive societies. Consider peace. In conflict-affected areas, where ASM tends to thrive, the sector provides marginalized youth and ex-combatants with a viable alternative to armed groups and criminal networks. Ex-combatants in Sierra Leone’s Kono region have reintegrated into society through artisanal gold and diamond mining; in eastern DRC, ASM keeps scores of young men out of rebel groups. Regarding inclusion, ASM communities generally accept people from all walks of life, irrespective of ethnicity and socio-economic status.

And the potential is far greater. As I demonstrate in a recent book chapter[1], ASM formalization can support long-term peacebuilding and state-building processes.

Peacebuilding and State-building through Formalization

By professionalizing and legitimizing historically marginalized livelihoods, ASM formalization can provide women and young men with more meaningful prospects for the future. For example, formalization can improve land tenure and labor rights and facilitate access to training, finance, and markets. As recognized by the UN Secretary-General, this is a critical step in preventing violent extremism among youth, and helps to address important root causes of the outbreaks of violent conflicts. (In Sierra Leone, frustrations over unemployment, exclusion and a general loss of hope for the future among youth have been identified as root causes of the decade-long civil war.)

Some formalization efforts are already helping to delink the ASM sector from insecurity. For example, the ITSCI programme in the African Great Lakes Region, for which Pact is the field implementing partner, helps to create “conflict-free” supply chains for 3T minerals (tin, tungsten and tantalum) that avoid contributing to armed conflict, human rights abuses, child labor, and corruption – contributing to peace and security in insecure parts of the region.

Besides this, formalization can support state-building and state-reconstruction, by: collecting government revenues through taxes and royalties; strengthening the rule of law through monitoring and enforcement of mineral regulations; or decentralizing the issuance of mining licenses and related tasks to local governments, and building their capacity.

However, experience has shown that none of this occurs automatically. We have learned that formalization processes are only as meaningful as they are comprehensive and inclusive, and they are unlikely to yield the intended impacts on SDG 16 (and all other SDGs) unless the Goal is deliberately targeted.

In order to enable adequate formalization processes and unlock the sector’s full peacebuilding and sustainable development potential, ASM needs to be prioritized and integrated into peace, security, and development frameworks at global, regional, and national levels. With my co-authors of the ASM-SDG Policy Assessment, I urge policymakers and private partners to take up our concrete recommendations for unlocking this potential and turning ‘conflict minerals’ into a force for peace, justice, and inclusion.

The author of this guest article, Jorden de Haan, works with Pact’s Mines to Markets program in Nairobi, Kenya. He is a development practitioner specializing in the intersections of ASM, formalization, socio-economic development and peacebuilding in Sub-Saharan Africa.

[1] Mining, Materials, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): 2030 and Beyond (view chapter manuscript at DELVE or ResearchGate)