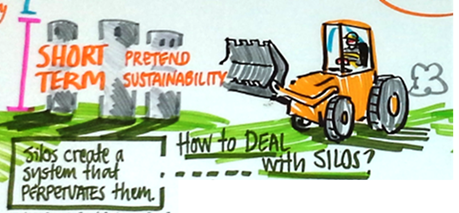

"Breaking down the silos" has become again a vivid call, even a mantra, in debates on governance for sustainable development and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in recognition of its comprehensive, holistic and systemic approach.

Silos are features of our institutions and can be very change-resistant; addressing them is a capacity building program in itself, related to peer learning, and will be beneficial for new global partnerships as well.

By Ingeborg Niestroy and Louis Meuleman

“Breaking down the silos” has become again a vivid call, even a mantra, in debates on governance for sustainable development and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in recognition of its comprehensive, holistic and systemic approach. A workshop on leadership organized by SITRA (Finland) in June, a blog post by Asa Persson (Stockholm Environment Institute) and sessions at the HLPF in July 2016 are just a few of the recent fora where silo-breaking has been addressed. But what is actually meant by it? What do people imagine when they call for breaking down the silos? Now that the HLPF has ended, it is useful to consider possible answers, to inform ongoing and future work on the ground.

We argue that while the SDGs require breaking down “mental silos” to allow for change, the common call to break down institutional silos poses risks. Institutions provide the necessary structure, reliability, transparency and communication points. Instead of breaking them down, we need to teach silos to dance.

Political, Mental and Institutional Silos

Conceptually, “breaking down the silos” reflects the long-standing call for policy integration and policy coherence: the former more coined in the legacy of environmental policy integration, the latter more specifically in the context of development policies, but also used as a wider term. In sustainable development and gender, for example, “mainstreaming” has become common terminology, underlining the need for broader integration, not only integrating environment into individual sectoral policies. Policy coherence seems to be an end, while integrating and mainstreaming are more the means to it.

We see three types of silos: political, mental, and institutional. In democracies, politicians need to win majorities. This comes with different degrees of competition and power struggles. Individual politicians tend to focus on their file and defend it, in order to raise their own profiles. This can lead to political silos. As political silos are almost inherent to the democratic system, there are limits to tackling them, which also depends on the political culture of the country. Some have constitutional arrangements that reduce or eliminate the decision-making power of individual Ministers (as in Sweden), or give a relatively strong (but still limited) “steering power” to the Prime Minister (as in Germany). In some countries, governments have experimented with so-called project ministers for cross-cutting issues that involve more than one ministry (e.g. the Netherlands).

In addition and often related, there are also mental silos: people have a firm belief that their problem definition and solution are not only the best, but even the only way forward. Different policy sectors like agriculture, transport and environment have their own world view and tend to operate in isolation. There are cultural, political, power-and career-related, cognitive and other reasons why people have ‘tunnel views’ and argue against change. However, for the comprehensive SDGs, for moving towards sustainable development with a need for policy integration and coherence, we need to step out of our comfort zones.

We also know that most governmental organizations (and in fact most large organizations) work as classical bureaucracies. They organize their work by dividing complex problems into more simple, partial problems, which are dealt with by separate sectoral or functional bureaucratic entities, which we tend to call “silos.” You become a civil servant in one silo, and typically stay within it. Exceptions apply in administrations where civil servants rotate across silos, as this is beneficial for careers (e.g. England; European Commission). Such institutional silos give people the room to work undisturbed, but may effectively prevent them from working with others, both within government and with stakeholders.

Most people probably think about these institutional barriers when they use or hear “breaking down the silos.” But what would this mean? Merging ministries? Putting everybody in one ‘super ministry’? And within one ministry: an organigram with all names in one box? Introducing flexible or matrix organisations, as experimented widely under the New Public Management banner, which is all about becoming more efficient and saving costs? Effectiveness, reliability and accountability are often lost on the way. Mergers of ministries have so far mainly taken place for short-term efficiency reasons in public-sector reform, and not with the aim of improving policy coherence. Merging ministries makes sense if you have 40 or 50 ministries in place to run the country. But if you are already down to around 20 (China), 15 (Georgia) or even 11 (Finland), further mergers can make governments much less effective.

©Annika Varjonen/Visual Impact Ltd, 2016

©Annika Varjonen/Visual Impact Ltd, 2016

What is Good about Institutional Silos

Without silos there is no focus, no structure, no accountability and no transparency. Institutional mergers may create new governance failures and threaten SDG implementation. Three benefits of silos are:

1. Silos represent positive features of government organizations such as clear lines of command, responsibility, focus on a given target and having internal “hotspots,” where expertise, memory and learning are concentrated. With respect to the SDGs, an accountable “silo” is needed in each country for, inter alia, reporting progress at the national level.

2. Silos have a different function and meaning in different administrative cultures. In Rechtsstaat cultures like Germany, and hierarchical ones in general, opening up silos has turned out to be more difficult than in consensus cultures like the Netherlands and Denmark, or in public interest models of government like in Australia, New Zealand and the UK (Pollit & Bouckaert 2011: 62-63). Hence, a closer look is required into how they operate, and a general verdict that silos are bad is culturally insensitive.

3. Silos provide clear, reliable and stable contact points within a ministry for partners and stakeholders. Without them, it can be difficult to develop enough trust that is needed to make a network approach work. Partnerships and participation increase the challenge of coordination, and thus require clear anchor points. Hence the common assumption that silos prevent stakeholder participation is questionable.

We should also keep our silos because there is no perfect alternative, and there may never be one. As Ulrich Beck developed in his “second modernity”: our time is so complex that we need to move from thinking in “best” tools, i.e. “either A or B,” to the approach of “A and B” (Beck, 1992). Such redundancies are also good for institutional resilience: if one tool doesn’t work, it is easier to switch to another.

The Alternative: Teaching Silos to Dance

Instead of breaking down institutional silos, we should strive to make them more flexible, permeable, interactive and transparent, while keeping their typical strengths and their specific functions in different administrative cultures. It remains a key approach for better policy integration to reinvigorate and improve horizontal coordination. Examples of such horizontal coordination arrangements are widespread, e.g. ‘inter-service steering groups’ (European Commission), state secretaries’ commissions or similar bodies for national sustainable development strategies (Germany, Finland), interdepartmental “dossier teams” (Netherlands), or cross-sectoral project teams. The SDGs reinvigorate the need to better bridge domestic and external policies, – a coordination task that has so far hardly been tackled.

While experience has been mixed, a key lesson is that coordination arrangements do not do the trick by sheer existence, but more efforts need to be put into how to run them. “We shouldn’t break the silos, but make them communicate better,” as Persson (2016) quotes a participant at an ECOSOC meeting. This requires a clever use of procedural tools for facilitating dialogue, with the aim to enable learning about others’ assumptions and objectives, building respect for other parties’ expertise, recognizing different professional competences and skills of other disciplines (including soft skills such as creativity, accuracy and analytical capacity). All of these can bring to bear the potential for cross-fertilization and new solutions.

A focus on facilitating dialogue, interaction and learning is at the core of opening mental silos. It will likely also require different leadership styles, e.g. switching from commanding to coaching, and capacity building for such adaptive leadership. Leaders will also need to allow, and even stimulate mistakes, as making mistakes is a normal feature of innovation.

Important for opening both mental and political silos are new narratives, such as sustainable production and consumption as presenting business and investment opportunities (see also Persson, 2016). New narratives as well as mutual gains approaches widen the perspective and enable awareness of synergies.

The SDGs as a system of goals provide a great opportunity to think along interlinkages, to identify trade-offs, but also synergies and knock-on effects. The nexus approach, with a focus on groups of connected goals, makes this manageable (see, e.g. Global Sustainable Development Report 2015 and 2016). Also impact assessments need to serve this better: On the one hand it is positive that in the European Commission’s comprehensive impact assessment of new policies, the economic, social and environmental impacts remain visible up to the very end. They are not “integrated away” into oblivion, but the individual assessments remain transparent. We recommend, however, to also develop assessments that show trade-offs and synergies, and with that provide a knowledge basis for better integrated decisions.

Translating the universal SDGs into national contexts requires “common but differentiated governance,” as different cultures and institutional traditions need to be taken into account (Meuleman & Niestroy, 2015). Similarly, there is no single “best” way to make silos more collaborative: each culture has unwritten rules about how people can work together.

To conclude: Silos are features of our institutions, mental comfort zones and political rationales, and they can be very change-resistant. Teaching elephants to dance (Belasco, 1991) has not been easy, and neither is teaching silos to dance. But we need to go for it. This is a capacity building program in itself, related to peer learning, and will be beneficial for new global partnerships as well.

Opinions in this piece reflect the personal views of the authors, Ingeborg Niestroy, IISD associate and affiliated with FU Berlin and PS4SD, and Louis Meuleman, Wageningen University (Netherlands), University of Massachusetts Boston and PS4SD

Contact: inge.niestroy@ps4sd.eu and louismeuleman@ps4sd.eu. Website: www.ps4sd.eu