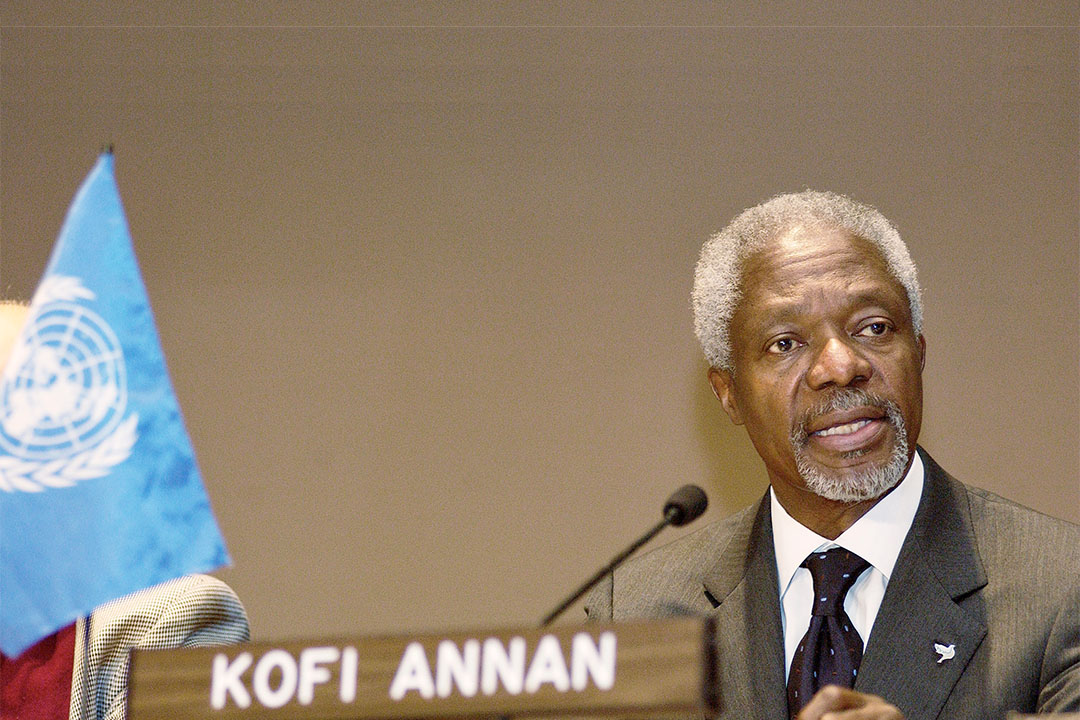

As many tributes have noted, former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan leaves behind a legacy of quiet, behind the scenes diplomacy from his tenure from 1997-2006. His achievements helped set the stage for the set of 17 universal sustainable development goals and 169 targets we have today. This brief looks at the SDG era that Annan helped usher in vis-à-vis his efforts to set and achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) as well as his vision for exceeding their ambition.

A proponent of people pushing their governments to act, Annan established the UN Millennium Campaign with an aim “to mobilize the world around the MDGs” and “rally all people” to make poverty history. Having founded the precursor to the SDG Action Campaign and collective efforts such as the upcoming Global Goals Week, Annan’s memory and work continue to live on.

A “committed internationalist,” Annan’s self-described greatest achievement was the MDGs, the first set of global targets to improve human development and ensure social well-being. Although the Millennium Declaration was signed by all 189 UN Member States in 2000, Annan convened a group of experts to ensure the Declaration led to action, tasking them with crafting what became the eight MDGs. The effort received criticism for being non-inclusive and yet another attempt by developed countries to decide “what was best for the rest of the world.” It reflects the opinion that Annan’s leadership style was “all general and no secretary.” But the MDGs offered a focus for development efforts and provided proof of concept that, when financial institutions, government aid agencies and other donors use a single framework to channel their efforts and guide action on shared objectives, targeted progress can be achieved.

Skeptics and globalists alike have questioned whether accelerating global progress on goal areas such as poverty reduction, health and education can be attributed to the MDGs. For example, China’s rapid economic growth is often credited with helping the world achieve the first MDG target on halving extreme poverty, but China is said to have paid “no attention” to the framework. Conversely, Africa’s increased growth rates, although uneven within and between countries, is often attributed to donor efforts and other MDG-aligned investments. Regardless of shortcomings on the goal-setting process, the Secretary-General’s personal style, or difficulties attributing improved well-being to the MDGs, Annan’s work helped set a guiding vision that articulated a world for which society should strive.

Always Forward-thinking

Drafted in 2000, the MDGs as we know them today effectively came into prominence during the 2002 UN International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD), called for by Kofi Annan and held in Monterrey, Mexico. In part due to Annan’s collaborating with an “unusually wide” set of actors, the summit resulted in the setting of a target whereby developed countries would contribute 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) as official development assistance (ODA) to developing countries. At the summit, Annan highlighted an increasing interdependence between rich and poor, stating, “we live in one world, not two… no one in this world can be comfortable or safe while so many are suffering and deprived.”

But Annan was not merely satisfied with commitments to increase aid. Prior to the 2005 G8 Summit in Gleneagles, Scotland he emphasized that “responsibility flows both ways” and “rich and poor alike must do their part.” This thinking has helped to shift discussions towards overcoming the North-South divide, and towards bringing high-income countries into the development agenda as more than just providers of finance. This convergence of countries working together towards a “shared destiny” is a key pillar of the 2030 Agenda adopted in 2015.

Ever forward-looking, a 2002 address by Annan framed sustainable development not as a burden or lifestyle reduction for developed nations, but as an opportunity that could “build markets and create jobs” – an opportunity that was quantified nearly 15 years later at more than US$12 trillion. Annan’s understanding of this opportunity, and that it would require collaborative efforts by diverse actors, is reflected in his 1999 proposal for and the subsequent launch of the UN Global Compact.

Looking Back to Look Ahead

Comprehending the scope and complexity of the SDGs can be aided by taking a look into the past. Returning to China’s experiences, development experts know which sectors in China grew fastest, who in the country benefitted, and what the consequences for the planet have been. We understand the gaps left by the MDGs and remaining challenges, such as on integrating environmental targets, ensuring action by all, and including good governance. We recognize that these issues, similar to economic growth and other standalone SDGs, can serve as launchpads for the others, and that progress in some areas may be pursued in ways that negate gains elsewhere.

Like the MDGs, the SDGs do not have an implementation guide, a project budget or an organizational chart that maps out responsibilities. The framework does, however, provide a common language for actors from every sector of society and region of the world to come together on shared challenges. In 2013, Brookings’ John McArthur penned an article on what the MDGs had accomplished, noting that previously, “there was no common framework for promoting global development.” The need to fill such a gap also speaks to the impetus behind the SDGs. At the turn of the millennium, rich countries were looking inward amidst a civil society backlash against globalization, with major multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organization and International Monetary Fund facing protests in the streets.

Society’s Next Steps and Annan’s Mark on the Transition to SDGs

A Financial Times article acknowledges that Annan’s “trademark optimism does sometimes seem misplaced in our turbulent times.” However, such optimism, as on display in his 2010 Der Spiegel Q&A, is a prerequisite to tackling the ambitious sustainable development agenda toward which global society has agreed to strive. Even if laggards remain, Annan noted in March 2017 that “the rest of the world will continue.” As demonstrated by the global response to the US announcing its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in June 2017, Kofi was right.

Annan also noted in Der Spiegel that building on lessons from the MDG era requires addressing root causes of key problems such as poverty, energy supply and climate change. With the SDGs’ ambition to “get to zero” on poverty and hunger, the goals of the Paris Agreement, and the AAAA, the 2015 agreements represent a “triumph for multilateralism” that still guides Member State actions, even if some are retreating. Complemented by initiatives such as Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All), which launched in 2011 and fed into the 2015 agreements, processes that Annan helped convene will continue to support the tackling of root causes. It is these root causes—ranging from gender and socioeconomic inequality to economic instability or marginalization to policy incoherence and siloed decision-making—that threaten the achievement of shared societal objectives.

Annan highlights a key lesson of the MDG era in the foreword of a 2015 paper: that the world’s challenges “cannot be achieved in isolation.” At a side event during the 2015 UN Summit to adopt the SDGs, Carlos Lopes described the need to move away from a “cappuccino approach” to development in which economic growth serves as the espresso base. Indeed, moving from MDGs to universal SDGs requires an integrated approach by all countries that cuts across economic, social and environmental pillars.

It is well-known that the SDGs demand action across the whole-of-society, supported by a wide range of means of implementation, including trade, technology transfer, data, capacity building and finance. Highlighting the importance of data to ending malnutrition in Africa, Annan continued to foster and promote the development of new tools that facilitate integrated SDG implementation and shift development paradigms. Similarly, on finance, mobilizing the private sector and “shifting the trillions” requires actors to be aligned with the spirit and principles of the 2030 Agenda. The UN Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI), launched in 2006 with Annan’s backing, offer a ready-made system to align institutional investors with the SDGs.

As one article reflected after Annan’s passing in August, if you care about the SDGs, then Kofi Annan “has played an important role in your work.” As members of the global community convene in New York for the 73rd UN General Assembly and largest-ever Global Goals Week, Annan’s legacy will be present in the ideals, spirit and foundational tools that are driving us towards the world we need.