By Åsa Persson, Stockholm Environment Institute

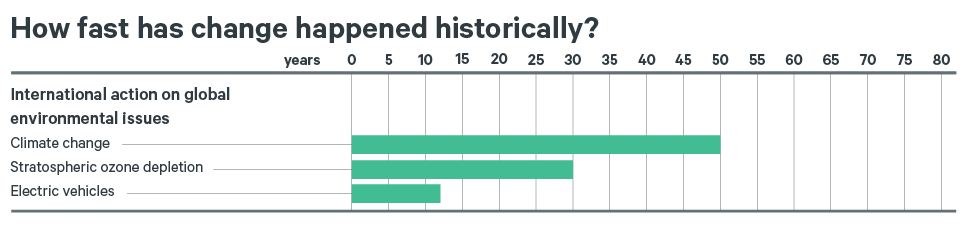

When adopted in 2015, the SDGs were a breakthrough in terms of integrating issues – the environment, economy, and society – that until then had largely been pursued in disconnected ways. The SDGs were also a breakthrough in terms of addressing equity by promoting the need for people, communities, and countries of different income levels to work together. But the SDGs have yet to make a breakthrough feature of one important aspect of the agenda: time dimensions. These dimensions must receive more attention and action, particularly now as we find ourselves at the halfway point of a mission begun in 2015 to achieve an agenda whose target date arrives in 2030.

The relatively recent rise of the issue of intergenerational equity on the Agenda amplifies this point. Youth movements are pushing for inclusion and action. The UN Secretary-General’s initiative, Our Common Agenda, focuses on the future, emphasizing “a deepening solidarity with the world’s young people and future generations.” Recent UN policy briefs outline possible actions “to think and act for future generations” and engage youth in the UN system. Negotiations for a new Declaration for Future Generations are starting. Indeed, equity between generations and the need to protect future generations’ rights were recognized when the 2015 resolution came into being. This, however, is only one of the time dimensions that must be addressed.

Examining what can be sustained over time

Sustainable development, by its very definition, must ensure that development can be maintained over time. For example, will environmental effects of increasing consumption undermine the future stock of natural capital? Will drastic environmental policies be socially sustainable over time? Yet, most reporting efforts on the SDGs – whether in countries’ Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs), lower-level governments’ Voluntary Local Reviews (VLRs), or private companies’ sustainability reports – typically offer static snapshots that reveal which and how many SDGs are part of a current initiative. This approach carries a risk. Will the number of SDGs referred to become the implicit metric of “success”? It is less common to see analysis of whether a particular initiative or action is likely to be sustainable over time. More reporting that examines sustainability over time is needed to complement snapshot mappings of current initiatives and the extent to which they align with the 17 SDGs.

More work is also needed to understand how interlinkages between goals play out over time. For example, as the COVID-19 pandemic hit, many actors agreed in principle that the wisest option would be to pursue a “green recovery” – that is, using recovery spending for green purposes to help achieve both economic and environmental objectives at the same time. Instead, a clear “temporal hierarchy” of policy objectives emerged, with traditional economic objectives de facto prioritized in the short term over opportunities to promote environmental objectives over the long term.

Source: Adapted from ‘Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future,’ SEI and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), 2022

Setting concrete timelines

Though the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development sets the target year – 2030, national plans and other SDG-related documents seldom set concrete timelines leading up to that point. The paucity of timetables deters progress. We must pick up the pace. Step-by-step planning is needed to think about how to achieve or make significant progress towards achieving the SDGs by 2030. Plans should map how and when to move from making decisions to taking actions to examining impacts.

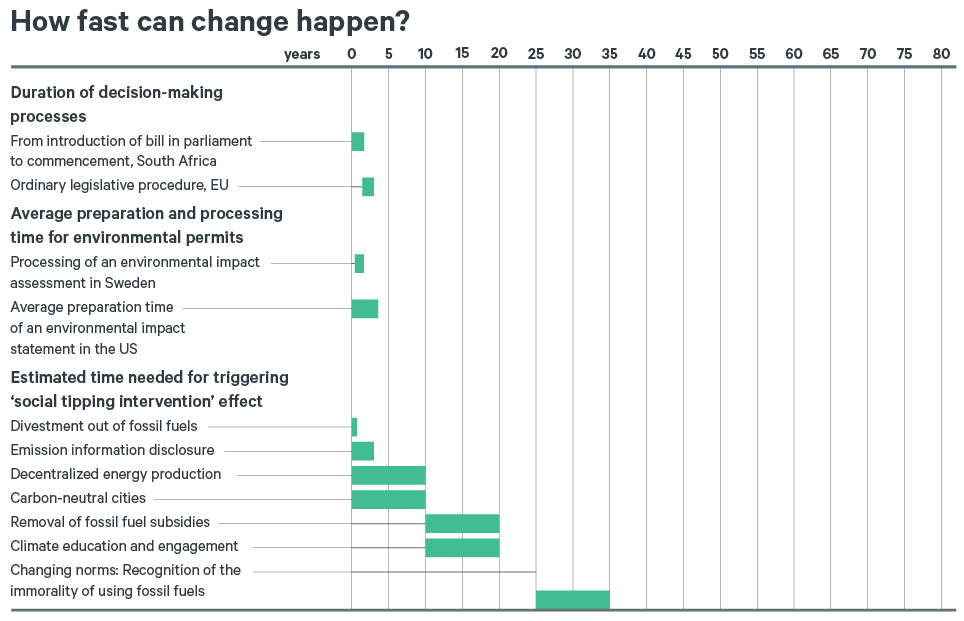

We must devise the sequence of actions that could shorten the timeline to see measurable effects and attain related goals. For example, how could an initiative on free school meals lay the groundwork for future policies on public procurement of sustainable food products? Should we invest more in the research and development (R&D) of sustainable food products today to ensure that alternatives are available to feed new markets tomorrow? Building on emerging analysis from a range of knowledge actors, the forthcoming 2023 UN Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR) focuses more on sequencing and understanding which levers would be most effective at which stage of transformation. Another action would be to ask VNRs to present timetables of planned measures to incentivize governments to reckon with the time horizon of the 2030 Agenda, and to internalize and prioritize the sequence of actions that should be taken over the remaining seven years.

Timetables must take into account the many steps involved in legislative and policy-making processes. To be democratically legitimate and robust, proposals first need to be conceived and analyzed. Proposals must undergo consultations. The ensuing legislative process can then take a couple of years, depending on the steps required and the institutions involved. Once legislation is in place, there may be a grace period, and, following that, implementation may take time to have impacts among the groups targeted. Lead times should be anticipated not just for new policies and initiatives to have an effect on the ground, but also for the preparatory decision-making process.

Source: Adapted from ‘Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future,’ SEI and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), 2022

Institutionalizing long-term thinking

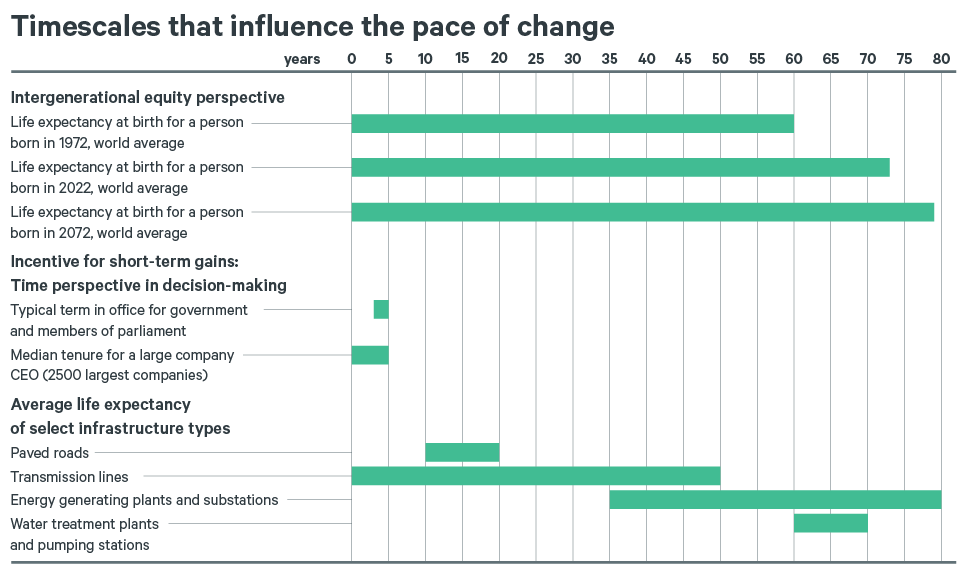

The world needs and deserves mechanisms to better account for the future and our future generations. At present, preparations for the 2024 Summit of the Future consider establishing a special envoy, a declaration, and a dedicated UN forum. A more promising way forward would be to pursue efforts to better institutionalize long-term thinking in government and in the private sector. This is the “Holy Grail” in public policy, where governments and parliaments come and go in four-year cycles, and electability in two, four, or six years is the driving motivation of many politicians. Business is not immune to short-termism either. Quarterly reports often dictate principles. The median tenure of a chief executive officer (CEO) of a large company is now typically five years.

As set out in our scientific report for Stockholm+50, we cannot rely on the good intentions of leaders to take a long-term perspective. We must better institutionalize longer-time horizons to inform the decisions we make today. Examples include mandatory procedures to assess the impacts that policies and regulations will have in a decade or even over a generation (25 years). Such an approach would be analytically and methodologically challenging but could open up for recognition of possible long-term risks and opportunities otherwise unaccounted for.

Another example is to rethink the practice of discount rates when making public investments. Why assume that return on investment is more valuable today than in the future? The inclusion of long-term thinking cannot rely simply on ad hoc visions or strategies set out by individual leaders. Long-term approaches need to be built into the legislative and procedural nuts and bolts of government machinery.

The 2030 Agenda offers the world an unprecedented global framework for sustainable development, in terms of its comprehensiveness, indivisibility, universality, and social legitimacy. It is the best guide we have. Let us not constrain our thinking, planning, and reporting to snapshots that capture images of SDG-aligned activities or action gaps that we see today. Let us instead strengthen our thinking and planning to foster development to benefit all in ways that can be sustained over time.

Source: Adapted from ‘Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future,’ SEI and the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), 2022

* * *

Åsa Persson is Research Director and Deputy Director of the Stockholm Environment Institute, and a Member of the Independent Group of Scientists drafting the UN 2023 Global Sustainable Development Report.

This perspective piece is part of a series authored by researchers from the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), published in partnership with IISD. In the series, SEI researchers examine ways to implement the 2030 Agenda without abandoning principles, diluting aims, or leaving people behind.