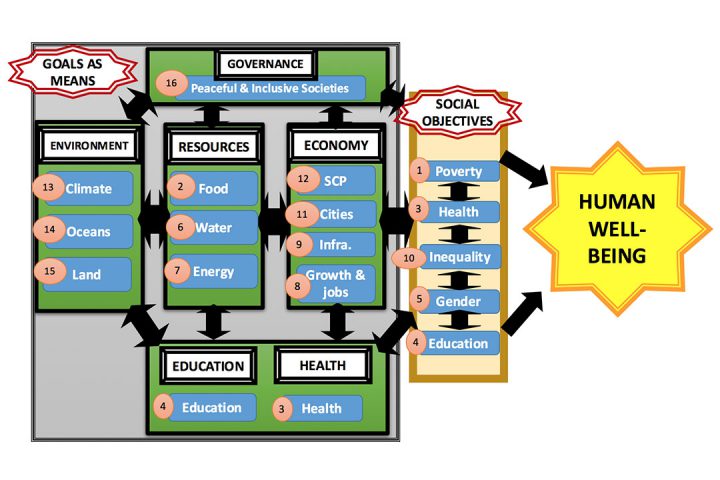

This article proposes a conceptual framework that identified five types of Goals, and explains the complex relationships among them.

Means-type goals can be classified into five categories, by function: resources, environment, education, economy, and governance.

Approaching the SDGs as a system where different goals play different roles can help to devise more effective implementation strategies and also to reduce the overall cost.

Implementing the 17 SDGs and their 169 targets can seem overwhelming, especially for developing countries. Finding sufficient means of implementation (MOI), in particular, is a daunting challenge; although the international community is mobilizing to provide assistance, the bottom line is that most countries will have to use domestic sources, or try to leverage private investment.

The SDGs call for an integrated approach, since there are many synergies and tradeoffs embedded within them, but the SDGs are so complex and disorganized that it is difficult to know where to start. Formally, means of implementation are treated separately from headline goals and targets in the SDGs. There is a separate headline goal on MOI and global partnership (SDG 17), and each of the other 16 SDGs each has a few targets designated as means of implementation. However, the means listed in SDG 17 are not all addressed systematically in the targets under the other Goals. The Addis Ababa Action Agenda on financing for development includes additional MOI which are not mentioned in the SDGs.

This article proposes a conceptual framework that explains the complex relationships among different kinds of goals. Approaching the SDGs as a system where different goals play different roles can help to devise more effective implementation strategies and also to reduce the overall cost.

Many Means to Achieve SDGs

Our key insight is that many of the so-called headline “goals” are actually means, and efforts to achieve these means-type goals need to be designed so that they contribute optimally to achieving the other “higher-level” final goals. For example, the water and energy SDGs (6 and 7) are not, strictly speaking, final goals. We do not want energy and water for their own sake, but because they are means to our true goals like health and well-being. Final goals might also include eliminating poverty, hunger, and inequality, although even these may be considered a means to a much broader goal of shared and lasting human well-being. Education and health, related to “human capital,” are worthy goals in and of themselves, but they are also clearly key means to achieving all of the other SDGs, as well as achieving means-related Goals like energy and water. Also, within individual goals, we can see a mix of means-oriented targets and targets oriented towards final goals. Therefore, the SDGs are in fact a complex chain of interlinked goals and means, and it is important to clarify these relationships in order to facilitate more effective and integrated implementation.

Many of the so-called headline “goals” are actually means, and efforts to achieve them must contribute optimally to achieving the other, higher-level final goals.

When deciding between different options to achieve means-type goals, it is essential to consider their expected contribution to higher-level goals. For energy access, for example, there is a broad range of technical and institutional options, but their influence on poverty alleviation, resilience, health, water consumption and climate impact can vary widely. If energy access is achieved through fossil fuels, then health might be undermined.

It is also important to note that some means-type goals may not contribute effectively towards achieving higher-level goals without additional efforts or policies in place. Strong GDP growth, for example, may not automatically generate many good quality jobs. In their effort to fuel growth, governments may be tempted to cut taxes on corporations and the wealthy, thus worsening inequality. And if governments weaken enforcement of environmental policies in order to attract investors and boost their profits, this could damage the environment while also undermining other social and economic goals, such as access to clean water and reduction of poverty and hunger.

Five Categories of Means-Type Goals

Means-type goals can be classified into five categories, by function: resources, environment, education, economy, and governance (see Figure 1). Resource goals include food, water, and energy (SDGs 2, 6, and 7). These resources are so important for human well-being that governments have elevated them to the status of goals. The resource goals have two main aspects, access, and environmental sustainability, and these two aspects may generate tradeoffs. These three resources are also interlinked, since they are needed to produce each other, as explained by the “nexus” concept. A significant amount of energy is needed to produce and treat water, while a significant amount of water is needed to produce energy.

Figure 1:

The second category, environment, includes ecosystems and natural capital, which, are the source of resources. Climate, oceans, and land (SDGs 13, 14, and 15) are the main SDGs that highlight environmental issues. Water also could be considered part of the environment, and the food goal (SDG 2) includes a target on sustainable agriculture. In terms of trade-offs, resource extraction often causes GHG emissions and other forms of pollution.

Education, the third category, plays a key enabling role, as does health. Efforts to promote these goals (SDGs 3 and 4) will directly contribute to most or all of the other SDGs.

The fourth category, economy is the key means for extracting resources from the environment, and for transforming resources into goods and services needed for achieving social objectives. This is based on a very broad conception of the economy, including both private and public economic activity as well as the accompanying institutions and regulations. The economy is the main source of jobs, and it is also the main means to allocate resources, which influences levels of inequality. Transformation of the economy towards sustainable consumption and production (SCP) (SDG 12) will thus be a key to achieving the SDGs as a whole. SCP should be the key organizing principle of the economy.

Governance is the fifth category. The word “governance” is not mentioned directly in the SDGs, but SDG 16 on peaceful societies is generally considered the “governance SDG.” Governance is a key means to enable and coordinate implementation of the SDGs, although the broader concept of peaceful societies is certainly also a final goal in itself.

This five-part conceptual framework helps to make the SDGs less complex and more understandable, and to show their interlinkages more clearly. Especially, it becomes much easier to visualize concretely how the SDGs support each other and recognize that a piecemeal approach to implementation would not be very effective.

This framework also makes it easier to identify missing or de-emphasized issues. Although 17 SDGs and 169 targets may seem like a lot, in fact, they are not fully comprehensive. For example, air pollution is de-emphasized (as part of targets 3.9 and 11.6) in contrast to the headline status of land, oceans, and climate (SDGs 13–15). The most important resources may be energy, water, and food, but they are not the only ones, and others, such as metals and minerals, are not included at all. Metals and minerals are critical inputs for the economy, especially for industrialization (in SDG 9) and renewable energy (in SDG 7), and current approaches to their extraction are responsible for significant water and land pollution (in SDGs 6 and 15) and air pollution as well as related health problems (SDG 3). Key aspects of governance are not reflected in SDG 16 on peaceful societies.

Understanding that many of the SDGs are mainly means has two important benefits. First, it can reduce the perception of how much means of implementation will be needed to achieve the SDGs. Second, it facilitates an integrated approach to implementation by clarifying broad synergies as well as tradeoffs. For example, investments in sustainable agriculture (in SDG 2) and integrated water management (SDG 6) will contribute to better health (SDG 3). By seeing more fully how the SDGs are related to each other, and how to implement the SDGs in a more integrated way, we avoid having to choose between allocating efforts, for example between SDG 7 on Energy and SDG 13 on Climate, which should be implemented as a package. This way of thinking can also help prioritization, by identifying a few key SDG targets that are likely to positively influence a range of other targets. Overall, this conceptual shift can help to increase effectiveness and reduce costs, making the SDGs much easier to implement for developed and developing countries alike.

This article is based on Elder, Mark, Magnus Bengtsson, and Lewis Akenji. 2016. ‘An Optimistic Analysis of the Means of Implementation for Sustainable Development Goals: Thinking about Goals as Means.’ Sustainability 8 (9): 962–86. doi:10.3390/su8090962.

Figure 1 was originally published in Elder, Bengtsson, and Akenji 2016.