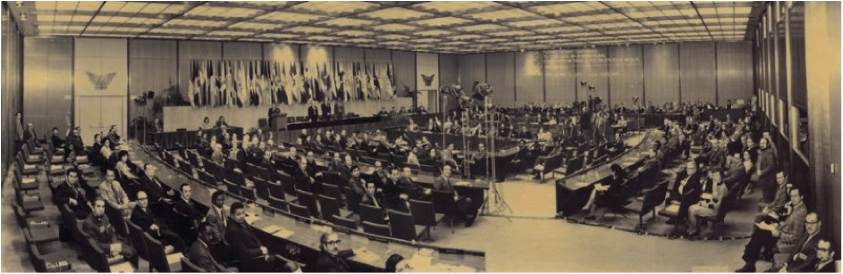

CITES was the third global environmental agreement to be adopted in the early 1970’s, signed in Washington DC, US on 3 March 1973 – and 3 March is now celebrated each year as UN World Wildlife Day. It was, however, the first such global agreement to enter into force on 1 July 1975, some six months earlier than the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and the World Heritage Convention.

CITES was the third global environmental agreement to be adopted in the early 1970’s, signed in Washington DC, US on 3 March 1973 – and 3 March is now celebrated each year as UN World Wildlife Day. It was, however, the first such global agreement to enter into force on 1 July 1975, some six months earlier than the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and the World Heritage Convention.

CITES is a legally binding agreement that is regarded as one of the most successful of all international environmental agreements, and interestingly, the Encyclical Letter of the Holy Father Francis on Care for Our Common Home references the importance of enforceable international agreements (see paragraph 173) and makes a positive reference to CITES (see paragraph 168).

CITES is a legally binding agreement that is regarded as one of the most successful of all international environmental agreements, and interestingly, the Encyclical Letter of the Holy Father Francis on Care for Our Common Home references the importance of enforceable international agreements (see paragraph 173) and makes a positive reference to CITES (see paragraph 168).

Since 1975, the world has witnessed growing prosperity, changing consumption and production patterns, vastly enhanced scientific knowledge, phenomenal advances in technology and, above all, exponential growth in global trade.

Looking at population figures alone, the world’s population has grown from 4 to over 7 billion people – and that is an additional 3 billion potential consumers of wildlife and wildlife products.

CITES therefore remains as relevant today as when it first entered into force 40 years ago. It is a living, breathing convention and one that has evolved over time in response to these changing conditions.

It has done so in many ways, including through bringing new marine and timber species under CITES trade controls, making the best use of emerging technologies and strengthening cooperative enforcement efforts.

Looking at CITES and shark species, none of which were listed under CITES in 1975, helps to illustrate the point. As it turns out, CITES entered into force within days of the release of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster movie ‘Jaws‘ in June 1975, which reflected Hollywood’s portrayal of the great white shark. Jaws is said to have perpetuated negative stereotypes and public misunderstandings about the role of sharks and their behavior. These perceptions have been changing, however, especially in light of the science on the unsustainable harvesting of some shark species that could drive them to extinction.

Looking at CITES and shark species, none of which were listed under CITES in 1975, helps to illustrate the point. As it turns out, CITES entered into force within days of the release of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster movie ‘Jaws‘ in June 1975, which reflected Hollywood’s portrayal of the great white shark. Jaws is said to have perpetuated negative stereotypes and public misunderstandings about the role of sharks and their behavior. These perceptions have been changing, however, especially in light of the science on the unsustainable harvesting of some shark species that could drive them to extinction.

It is within this context of changing perceptions and better science that CITES intervened to bring eight species of sharks under CITES trade controls in recent years, including five species in 2013, to ensure that any international trade in these species is legal, sustainable and traceable.

It is within this context of changing perceptions and better science that CITES intervened to bring eight species of sharks under CITES trade controls in recent years, including five species in 2013, to ensure that any international trade in these species is legal, sustainable and traceable.

The enduring relevance of CITES was perhaps most powerfully expressed through the agreed outcomes of the UN Conference on Sustainable Development or Rio+20 in 2012, where the Convention was described as “an international agreement that stands at the intersection between trade, the environment and development.”

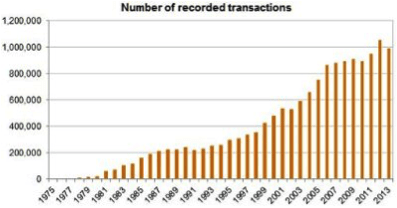

This was an apt description of CITES, which is highlighted by the fact that a significant amount of wildlife and wildlife products are legitimately traded each year under CITES, with such legal and sustainable trade often having benefits for both wildlife and people, such as the trade in the wool of the vicuna, meat of the queen conch and bark of the African cherry tree. And CITES has just recorded its fifteen millionth trade transaction in its trade databases.

This was an apt description of CITES, which is highlighted by the fact that a significant amount of wildlife and wildlife products are legitimately traded each year under CITES, with such legal and sustainable trade often having benefits for both wildlife and people, such as the trade in the wool of the vicuna, meat of the queen conch and bark of the African cherry tree. And CITES has just recorded its fifteen millionth trade transaction in its trade databases.

Over recent years, however, we have been experiencing a surge in illegal trade in wildlife – or wildlife that is traded in contravention of CITES, especially as it affects elephants, rhinos, pangolins and some precious timber species. This illegal trade is global in nature, is taking place at an industrial scale, involves transnational organized criminal gangs and rebel militia and it is having devastating economic, social and environmental impacts.

Over recent years, however, we have been experiencing a surge in illegal trade in wildlife – or wildlife that is traded in contravention of CITES, especially as it affects elephants, rhinos, pangolins and some precious timber species. This illegal trade is global in nature, is taking place at an industrial scale, involves transnational organized criminal gangs and rebel militia and it is having devastating economic, social and environmental impacts.

The importance of CITES in combatting illegal trade in wildlife and facilitating legal and sustainable trade, should a country wish to trade in a species that can be traded under CITES, is greater than it ever was.

The reasons for the ongoing success and relevance of CITES are many and varied, but perhaps there are three reasons that stand out most.

The first is the quality of the original text of the Convention adopted in 1973 and its evolution over time. It is focused, pragmatic, and establishes a robust international regulatory regime to address international trade in wild plants and animals. It is a regime that has stood the test of time, and just last week the Director General of the WTO and I released a joint CITES-WTO publication on the relationship between the WTO and CITES as a leading example of how global trade and environmental regimes can support each other and cooperate successfully to achieve shared goals. The publication highlights that there has never been any WTO dispute directly challenging a CITES trade-related measure.

The first is the quality of the original text of the Convention adopted in 1973 and its evolution over time. It is focused, pragmatic, and establishes a robust international regulatory regime to address international trade in wild plants and animals. It is a regime that has stood the test of time, and just last week the Director General of the WTO and I released a joint CITES-WTO publication on the relationship between the WTO and CITES as a leading example of how global trade and environmental regimes can support each other and cooperate successfully to achieve shared goals. The publication highlights that there has never been any WTO dispute directly challenging a CITES trade-related measure.

Secondly, robust partnerships have been forged in the implementation of the Convention with a broad range of entities both within and outside of the UN and with both governmental and non-governmental bodies. This has been a strong focus over the last five years, in particular with the establishment of the International Consortium on Combatting Wildlife Crime (ICCWC), a joint initiative of the CITES Secretariat, INTERPOL, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Bank and the World Customs Organization (WCO) – as well as through partnering with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) on implementing the listing of sharks and manta rays, and the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) on implementing listings of tropical timber species.

Secondly, robust partnerships have been forged in the implementation of the Convention with a broad range of entities both within and outside of the UN and with both governmental and non-governmental bodies. This has been a strong focus over the last five years, in particular with the establishment of the International Consortium on Combatting Wildlife Crime (ICCWC), a joint initiative of the CITES Secretariat, INTERPOL, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Bank and the World Customs Organization (WCO) – as well as through partnering with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) on implementing the listing of sharks and manta rays, and the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) on implementing listings of tropical timber species.

Thirdly, and most importantly, is the deep commitment of the 180 Parties to CITES – soon to be 181 – to implement the Convention by putting into place national-level Management and Scientific Authorities, and enforcement measures, as well as through collaborative cross border efforts, which were recently highlighted by the combined efforts of 62 countries across Asia, Africa, America and Europe in undertaking the largest ever coordinated effort to combat illegal trade in wildlife, known as Operation Cobra III.

It is these national CITES authorities that are the engine room of the Convention and have ensured its success.

And now we pause to celebrate the Parties to CITES; we celebrate their vision and commitment from 1975 to today. It is a great example of successful international cooperation combined with national action that has lasted for four decades.

This visionary Convention is as relevant today, if not more relevant, as it was in 1975 in enabling us to continue to benefit from wild plants and animals – and now I quote from the founding text of the Convention itself – from the “aesthetic, scientific, cultural, recreational and economic points of view.”

This visionary Convention is as relevant today, if not more relevant, as it was in 1975 in enabling us to continue to benefit from wild plants and animals – and now I quote from the founding text of the Convention itself – from the “aesthetic, scientific, cultural, recreational and economic points of view.”

The article was authored by John E. Scanlon, Secretary-General, Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).